QuranCourse.com

Muslim governments have betrayed our brothers and sisters in G4ZA, standing by as the merciless slaughter unfolds before their eyes. No current nation-state will defend G4ZA—only a true Khilafah, like that of the Khulafah Rashideen, can bring justice. Spread this message to every Muslim It is time to unite the Ummah, establish Allah's swth's deen through Khilafah and revive the Ummah!

Fiqh Al Zakah by Dr. Yusuf al Qardawi

3.2 Chapter Two Zakah On Livestock

The animal kingdom has many species. Mankind has made use of only a few of them. This is what is known by Arabs as al an'am. Camels, cows, buffalo, sheep, and goats, are all part of what God bestowed on His servants. Their benefits are mentioned in several places in His Holy Book. In sura al Nahl - sometimes called sura al An'am (livestock) - God says "and cattle He has created for you, from which ye derive warmth, and numerous benefits, and of their meat ye eat. And ye have a sense of pride and beauty in them as ye drive them home in the evening, and as ye lead them forth to pasture in the morning, And they carry your heavy loads to lands that ye could not otherwise reach except with souls distressed, for your Lord is indeed most kind, moat merciful,"1 Also "and buried in cattle will ye find an instructive sign, from what is within their body between excretions and blood, we produce for your drink, milk, pure and agreeable to those who drink it,"2 "and made for you, out of the skins of animals, tents for dwellings, which ye find so light and handy when in travel and when ye stop, and out of their wool, and their soft fibers, and their hair, furniture and articles for all convenience to serve you for a time"3. In sura Yasin, "See they not that we have created for them among the things which our hands have fashioned, cattle which are under their domination. And that we have subjected them to their use: of them some do carry them and some they eat, and they have other profits from them besides, and they get milk to drink. Will they not then be grateful?".4 God fashioned this livestock for mankind, and He subjects then to humans to ride and to make use of their skin and hair. It is not surprising that God asks people to be thankful.

The most obvious and practical thankfulness urged by the Holy Qur'an and the purified tradition of the Prophet (p) is the obligation of zakah. Its nisab and rates are determined, collectors are sent every year to owners of cattle, and warning to those who refuse its payment is put forth. Livestock, especially camels, were the most useful asset for the Arabs at the time of the Prophet (p). Consequently, Sunnah determined their nisab and rates very clearly. In many countries today especially Muslim countries, livestock still represent one of the most important national assets and source of income.

The following sections attempt to provide full account of zakah on livestock.

SECTION ONE GENERAL CONDITIONS FOR ZAKAH ON LIVESTOCK

Zakah is not imposed on livestock of all quantity and kind. There are certain conditions that should be fulfilled for the zakatability of livestock which are ennumerated here:

1. The minimum for zakatability (Nisab)

The first condition is nisab, since zakah is only on the rich, and not every owner of livestock is rich. There always should be a limit above which persons are considered rich. This limit is nisab. It is five camels by unanimous agreement of Muslims for centuries. There is no obligated zakah for anything below five camel, nisab for sheep is forty sheep, also unanimous. Nisab is determined by sayings of the Prophet (p), by his actual practice and by the application of his successors. Nisab for cows varies from five to thirty-two to fifty, depending upon the school of jurisprudence one adopts.

2. The passage of a Year (Annual)

This is reported authentically from the Prophet (p) and his successors. They used to send zakah collectors once every year to take the count on livestock. It was shown in the previous chapter that the condition of the passage of one full lunar year for non-earned assets is accepted unanimously. One can add here that the majority who assert this condition on earned income do not require it on the offspring of livestock that result from reproduction during the year, and accept the zakatable year for offspring to be that of their mothers.

3. They should be pastured naturally

Pastured livestock are those that are grazed on natural and cost-free pasture land during the major part of the year for the purpose of breeding, milking, and putting on weight.5 The opposite of natural grazing is buying feed.

The condition is satisfied if livestock is pastured naturally most of the year.

Pasturing should be made for the purpose of growth, reproduction, and milking; thus if it is made for the purpose of personal riding or eating, these animals are not zakatable, since such allocation removes animals from being growth assets and put them in the category of personal use which is not zakatable as shall be shown in the next subsection.

The reason for this condition is that zakah is obligated on the surplus, what is easy for persons to pay, in accordance to the verse, "take the surplus"6 and the verse "when they ask you what to spend, say the surplus"7, that is, on what does not cost much and grows rapidly. This can only be fulfilled if the animals pastured cost-free, since artificially fed animals have high cost, which makes it hard for people to give then away as zakah.

This condition is derived from what is reported by Ahmad, al Nasa'i, and Abu Daud from Bahz bin Hakim from his father from his grandfather, who said: I heard the Messenger of God (p) saying about naturally ( cost-free ) postured camels, for each forty, there is one as zakah ... etc. "This saying is graded correct by a group of leading scholars. The adjective "naturally, cost-free pastured" here implies that artificially fed camels are not subject to zakah; otherwise adding such an adjective becomes meaningless, and the Prophet (p) does not speak in vain. It is obvious from this saying that camels characterised, as naturally, cost-free pastured are unlike those that are not.

Al Khattabi comments, "When something may have either of two characteristics, and a ruling of Shari'ah is applied to one of them, then the opposite ruling applies to the other characteristic, by implication".8 It is also accepted by scholars of the methodology of jurisprudence that giving a specific characteristic in a ruling implies that when the characteristic is absent the ruling does not apply9 i.e., camels fed by purchased feed are treated differently.

This saying is further supported by a report is the correct collection of al Bukhari and others from Anas, that "if sheep are naturally (cost-free) pastured, and reach 40 in number, there is one sheep as zakah". If the condition of natural free pasture is required on sheep it should also be, by analogy, required on camels and cows, since there should be no distinction between them. Sayings without such restriction should be taken with reference to those that came with the restriction of natural free grasing.

This is the opinion of the majority of scholars, Rabi'ah, Mlaik and al Layth differ on that. They obligate zakah on manually fed livestock the same way it is on naturally pastured, as implied by the sayings that do not have the restriction. Their explanation of the restricting sayings is that the word "natural or cost-free pasture" is a general description because this was a common adjective of livestock at the time of the Prophet (p).10

4. Zakatable livestock should not be working animals

This is the fourth and last condition for zakatability of livestock. It means that they should not be used for cultivation, carrying water or loads or riding, etc. This condition only applies to camels and cows. Abu Ubaid reports from 'Ali, that " There is no sadaqah on working cows."There is also a report that Jabir bin 'Abd Allah said "Animals working in cultivation are not zakatable."11 Abu Daud, in his Sunan, reports from Zuhair "We are told by Abu Ishaq from 'Asem bin Damurah and al Harith from 'Ali, (Zuhair said "I think from the Prophet") that he said, "Bring me one-fourth of a tenth, i.e. on each forty dirhams one dirham..." and he continued, "and there is nothing due on working animals." This is reported also by Ibn Abi Shaibah linked to the Prophet, and by 'Abd Al Razzaq, in his Musannaf, via al Thawri and Mamar as from 'Ali only.12

Similar reports exist as coming from Ibrahim, Mujahid, al Zuhri, Umar bin 'Abd al Aziz, and some other Followers.13 It is also the view of Abu Hanifah, al Thawri, al Shafi'i, and the Zaidis. It is the opinion of al Layth as far as cows are concerned.

Two things support these narrations and this point of view. The first is the principle that assets designated for personal use and service are not zakatable, and by the same token livestock designated for cultivation, or personal transportation should not be zakatable. It is apparent that such animals are not part of the assets invested for growth.14 Secondly, the report of Abu 'Ubaid from al Zuhri, that cows and camels used for carrying riders are not zakatable, and neither are cows used for cultivation.15 All these are like tools for agriculture, Sa'id bin Abd al Aziz al Tanukhi says "Cows used in cultivation are not zakatable, because the grain produced is being zakated, and it involves the work of cows.16 If animals used in the process of farming were to be zakated, zakah would then be double on agriculture, taken once on the means of production and again on the produce, as rightly stated by Abu 'Ubaid. Malik disagrees with the majority on this ruling, and according to him zakah is obligated on cows and camels, working or not, naturally pastured or not. When the view of Malik was mentioned to al Thawri he replied "I did not think that anyone would say that".17 In fairness, one should add that some Malikite jurists lean toward the view of the majority.

Ibn Naji quotes lbn 'Abd al Salam as saying "In this regard, the view of the majority is the one that one feels more comfortable with." Abu 'Umar bin 'Abd al Barr shows that Maliketes' view on working animals is in conflict with their position on jewelry designated for personal use; the latter is not zakatable, according to them.18

SECTION TWO ZAKAH ON CAMELS

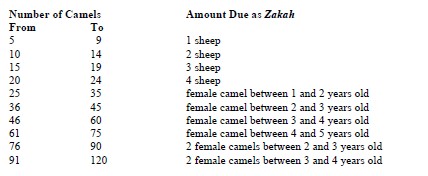

The unanimous agreement of Muslims, as well as several correct sayings of the Messenger of God (p) and reports from his Companions indicate nisab of camels and the rates of nisab on them are as follows:

There is ijma on this schedule,l9 except for a report from 'Ali that on 25 camels there is five sheep and on 26 camels there is one female camel between one and two years old.20 Ibn al Mundhir says. The unanimity is net broken, because what is reported from 'Ali is not authentic. The saying of Anas on these quantities and amounts is correct and there is a unanimous agreement on its content.21 For more than 120 camels the majority's view is that for each additional 50 camels the additional amount of zakah is a female camel between three and four years old while on each additional 40 camels the additional amount of zakah is a female camel between two and three years old.22 This is shown in the following table :

It is seen from the table that for big numbers, an increase of less than ten camels does not affect the amount of zakah. Once it is increased by ten, then you go one step higher in the amount of zakah due according to the same rule mentioned above. It is obvious from these two tables that if the number of camels owned is less than five then there is no zakah. Once they reach five , the amount due is one sheep. The author of al Mabsut quotes a scholar as saying, "this means that the value of the livestock is considered. Camels between one and two years old used to be priced at forty dirhams and a sheep at five dirhams, so five camels equal 200 dirhams also equal 40 sheep. This implies that the minimum for zakatability of camels, sheep, and silver money is the same. Ibn al Humam in al Fath and Ibn Nujaim in al Bahr reply, there is a saying that states "Whoever is obliged to give as zakah a camel of a certain age group, but does not own any in that age, can pay in substitution on the average of 10 dirhams for a sheep, if he does not have a sheep. This is an explicit text that contradicts the explanation of al Sarakhsi.24 The saying referred to is reported by al Bahr from Anas.

Shari'ah obligates sheep as zakah on camels if the number of zakatable camels is lees than 25, though usually zakah is paid out of the same kind of the zakated assets.

The reason is obviously that the amount due is less than one camel, but at the same time Shari'ah considers five camels to sufficiently define who is rich.25

Numbers and amounts in the above two tables come from the actions of the Messenger of God (p). Al Nawawi in al Majmu' says that the quantities and amounts of zakah on livestock come from the two saying narrated by Anas and Ibn 'Umar.26

Anas narrated that Abu Bakr, the Truthful wrote this message when he sent him to Bahrain:

In the name of God, most merciful, most gracious. This is the obligation of sadaqah imposed on Muslims by the Messenger of God (P), as ordained to him by God.

Whoever is asked to pay it according to these rules must give it, and whoever is asked to pay more should refuse. On each 24 camels or less, zakah is due in sheep. On each five camels, one sheep is required. Once they reach 25 and up to 35 one female camel, one to two years old, is required. From 36 to 45, there is one she-camel two to three years old.

If they reach 46 to 60, there is one she-camel three to four years old due, one that can be bred. If they reach 61 to 75, one she-camel four to five years old is due. If they reach 76

to 90, there is two she-camels two to three years old due. If they reach 91 to 120, there are two she-camels, three to four years old due. If they are more than 120, for each 40

there is one she-camel two to three years old, and for each 50 there is one she-camel three to four years old. A person who owns [up to] four camels is not zakatable unless he volunteers, but if they reach five camels, one sheep is due on them as zakah. In the sadaqah on sheep, if they are naturally, cost-free pastured, and number between 40 and 120 sheep, there is one sheep due. For more than 120 and up to 200, there are two sheep.

For more than 200 up to 300 there are three sheep. For more than 300, the amount of zakah is one sheep for each 100 or a fraction therein. If a person owns less than 40

naturally cost-free pastured sheep, there is no sadaqah unless the person wishes to volunteer. On mint currency there is one-fourth of one-tenth due . If a person own only 190 dirhams27 there is nothing on them except by the voluntary initiative of the owner".

The letter further states, "The person whose zakah is a female camel, one to two years old, and who has none of that age , but one in the next higher age bracket, it is acceptable, and the zakah collector returns to him the difference, twenty dirhams or two sheep. If he owes a she-camel one to two years old but does not have it, a male camel between two and three years old is accepted in its place. A person who owes as zakah one she-camel four to five years old and has none in that age group, but has a she-camel one year younger, may pay the younger along with two sheep if available, or twenty dirhams. A person who owes as zakah one female camel three to four years old and does not have any in that age bracket can pay one female camel in the next higher age bracket and the collector then returns to him 20 dirhams or two sheep. Nor a person who is required to pay sadaqah in the amount of one female camel three to four years old and has only a female camel in the age group of two to three years old, it can be accepted from him, along with two sheep or 20 dirhams. For a person whose sadaqah should be one female camel two-three years old who has one a year older, it is an acceptable substitute the zakah collector returns to him 20 dirhams or two sheep. If a person sadaqah is one female camel two to three years old and he does not have it, but has one a year younger, it is acceptable as zakah along with 20 dirhams or two sheep.28 An old, damaged or defected animal is not accepted as zakah, nor should the collector take a ram unless it is volunteered as extra sadaqah by the zakah payer. What is divided should not be added together, and what is together a zakatable unit must not be divided in order to avoid zakah.29 For cattle owned by partners,30 partners would settle the account among themselves in proportion to their shares. Al Nawawi says "this letter is reported by al Bukhari in his correct collection, scattered throughout the chapter on zakah. I put it back together."31 It is also reported by Ahmad, 'Abu Daud, al Nasai and al Daraqutni.

The latter adds "The chain is correct and the narrators are all trustworthy," as in al Muntaqa.32 Al Shaukani says "It is also reported by al Shaukani, al Baihaqi, and al Hakim, Ibn Hazm says this message is maximum in correctness. It is also graded correct by Ibn Habban and others.33

The saying from Ibn 'Umar, is narrated by Sufian bin Husain from al Zuhri from Salim from his father, 'Abdullah bin 'Umar: The Messenger of God (p) wrote the message on sadaqah but did not send it to his commissioners until he died. He tied it to his sword, and when he died, Abu Bakr applied it until he died, and then 'Umar, until he died. The letter contains "For five camels there is one sheep due, for ten, two sheep.."etc, continuing with the same rates listed in the saying from Anas. Al Nawawi said it is reported by Abu Daud and al Tirmidhi, who marks it a good saying.34 Al Shaukani adds "This saying is reported also by al Daraqutni, al Hakim and al Baihaq".35

Ibn Hazm says in his commentary on the saying from Anas "This saying is maximum in correctness. The Truthful Abu Bakr applied it in the presence of all the Companions, and none of them is known to have disagreed at all, although ijma' is usually claimed in much lees unanimitty than this."36 The great majority of scholars of this nation have received these messages with acceptance, and practically apply them, although some of the leading scholars of hadith, such as Yahya bin Ma'in hesitate in considering them correct, in consistency with his special approach in scrutinising narrators and the links among them.

It seems that the Orientalist Schacht abuses the stand of Ibn Ma'in in order to shed doubt on all the sayings on zakah and the whole institution itself. He claims that the jurists' opinions on the issue have their stamp on the saying itself, and adds "we note, in this respect, that the detailed system of zakah commonly attributed to Abu Bakr is sometimes attributed to the Prophet (p), to 'Umar bin al Khattab, or 'Ali bin Abi Taleb".37 Schacht is known for his hostility toward the traditions of the Prophet (p).

Very often he fabricates reasons to shed doubt on them and to disorient the reader about them. In his books he collects all the misinterpretations and misleading statements and the fabricated and false misrepresentations against the Sunnah. I thank God that my dear and respected colleague, Dr. Muhammad Mustafa al Azami threw these falsehoods back in the face of their author in his extensive study on hadith in English, which was submitted to Cambridge University as his Ph.D. dissertation.38 It showed that to be fair and reasonable, the Orientalist should have realised that it is extremely unlikely that the Prophet (p) would leave such an important issue like zakah on camels, sheep, etc., without determining its minimums and its rates, since this was where the majority of the wealth of the Arabs at his time lay. The zakah collectors and commissioners were sent by him to oasis and deserted areas to collect and distribute zakah every year from the scattered tribesman. There are many reports about sending those collectors and the way they were told to treat zakatable individuals, what to take, what not to take, what the response of cattle owners should be and how they should treat the collectors. No fair and reasonable researcher can claim that all these sayings are fabricated on behalf of the Messenger (p).

It is no surprise that the Prophet (p) sent instructions determining nisabs and rates of zakah on cattle and other growing items of wealth that were most dominant at his time and within his environment. This is testified by the message of instruction of Abu Bakr as well as in that of 'Umar, and both of them are linked to the Prophet (p). It was shown in the previously quoted message of Abu Bakr that "This is the obligation of sadaqah that the Prophet of God (p) imposed on Muslims..,". The letter written by 'Umar, and narrated by his son, Abd Allah reads "Verily the Messenger of God (p) wrote the letter of instructions on sadaqah..." As for the letter of inetruction of 'Ali bin Abi Talib, there is no agreement among scholars about whether or not it was linked up to the Prophet (p).

This anyhow is not as famous as the letters of Abu Bakr or 'Umar, nor does it have the same strength of chain they do. It should be noted that these were not the only letters of instructions that provide details of zakah on livestock, There are several other messages, such as that of 'Amr bin Hazm which was addressed to the people of Najran, about the details of obligated zakah, and ransoms compensating accidental deaths or the loss of parts of the body. We have also the message of Mu'adh that delineates sadaqah on cows, and several other letters.

It is worth observing that all these instructions do not differ on certain major points, such as:

1. There is no zakah obligated on anything less than five camels.

2. There is no zakah on any number of sheep lees than 40.

3. There is no zakah on less than 200 dirham of silver.

4. The amount of zakah that is obligated on less than 25 camels is calculated in sheep.

5. Zakah on up to 25 camels is one sheep for each five camels.

6. They agree on the ages and number of camels due as zakah on the wealth of 25 to 120 camels.

7. They also agree on the rate of zakah on sheep from 40 to 300, and that the rate afterward is one for each 100.

8. The rate on silver and silver money is one-fourth of one-tenth.

9. Both damaged animals and the top quality animals are not taken as zakah.

What is required is animals of about average quality.

Those instructions do not agree, however, on certain minute and secondary details such as the rate on camels after 120. The instructions of Abu Bakr put the rate at one female camel two to three years old for each 40, and one female camel three to four years old for each 50, while the instructions in the letters of 'Ali and Amr bin Hazm start again with the same rate as that between five and 125. Also, these instructions do not mention some other items of wealth, such as gold money and cows. It seems to me that this itself provides us with some additional proof that these texts are rightly attributed to the Prophet (p), and that they were not influenced by the jurists' opinions as Schacht claims, because many detailed thoughts of jurists do not appear in these instructions.

The Prophet (p) was writing practical instructions to different people according to their needs and circumstances, he did not mention gold money because Arabs of his time did not frequently use it and did not mention cows because they were not common in Madinah. Only in his instructions to Mu'adh, who was being sent to Yemen, did the Prophet mention cows, because they were common in Yemen.

Variance on the Rates after 120 Camels

I pointed out earlier that there are varying views among jurists on zakah on above 120 camels. Malik, Shafi'i, Ahmad, and the majority consider the rate to be one female camel, three to four years old for each additional 50, and one female camel, two to three years old, for each additional 40,39 as mentioned in the message of Abu Bakr and 'Umar narrated successively by Anas and Ibn 'Umar. The same also appears in the messages of Ibn Hazm and Ziad bin Labid to the people of Hadramut,40 in the words of the Prophet (p) "If they exceed 120, then for each 40 one female camel two to three years old, and for each 50 one female camel three to four years old". Some versions of the last saying are summarized by that narrator, as "In each 50 one female camel ..." without mentioning the rate for each additional 40, but the different versions complete each other.

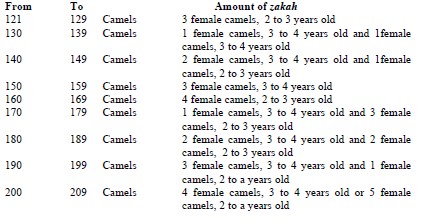

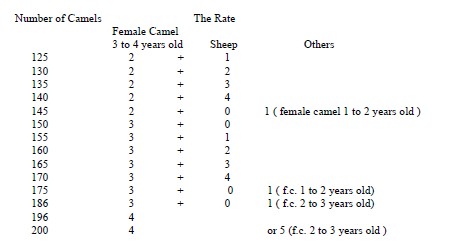

Abu Hanifah's view

Al Nakha'i, Al Thawri, and Abu Hanifah41 say that "for what is above 120, we start the rates from the beginning, i,e., for an additional five to 24 camels, the rate is one sheep for each 5 camels, and for an additional 25 camels zakah due is one female camel, one to two years old, etc."The following table shows the amount due according to this opinion:

After 200 the rate repeats itself, one sheep for each additional five camels, and each time the additional zakatable camels reach fifty, the amount of zakah due on it is one female camel three to four years old.

The Hanafites argue that Abu Daud reports as mursal [saying in whose chain the name of the reporting Companion is not mentioned], Ishaq in his Musnad and al Tahawi in his Mushkel from Hmmad bin Salamah, who said, "I told Qais bin Sa'd to get me the message of Mohammad bin Hazm, so he gave me a letter which he said he took from Abu Bakr bin Mohammad bin Hazm, who said that the Prophet (p), wrote it to my grandfather. I read it and found in it the rates of zakah on camels... " and he narrated the saying until, "Once they exceed 120 make due on each 30 one female camel three to four years old. For the increments, restart the rates from the beginning, and for what is less than 25 camel increments, the amount of zakah is due in sheep, one sheep for each five." This is reported in Nasb Al Rayah by al Zaila'i.42 A similar version is narrated by 'Asem bin Damurah from Ali, linked to the Prophet as well as ending at 'Ali,43 and Ibn Mas'ud is reported to have said similar things. The Hanafites are said by Ibn Rushd to have argued that such a thing cannot be decided but by instructions from the Prophet, because it is not anything that can be deducted by analogy.44

The majority of scholars disapprove of the arguments of the Hanafites and see weakness in their findings. Al Baihaqi shows that whatever is reported from Ibn Mas'ud in this matter is not correct.45 The version of the saying of 'Ali which is linked to the Prophet (p) is also incorrect, and there are also differing opinions on the version that is attributed to 'Ali. In one version it is reported in a consistent manner with the letters of Abu Bakr and 'Umar, while in another version it is reported differently. The usual applicable rule in such a case is that we give more weight to the version that is consistent with other correct sayings which are not disputed. This was noted by al Hazimi.46 Moreover, the same version of the saying (from 'Asem) contains a sentence all scholars agree to disregard because of its weakness. That is the statement that for each 25 camels the zakah due is five sheep instead of a one to two years old she-camel. On the other hand, it is possible to interpret those differing versions in a way that make then consistent with the other correct sayings.

As for the saying of Ibn Hazm, some scholars interpret the starting over of the rates as a reference to the calculation of the rates on additional 40 or 50 camels as mentioned in the two sayings of Abu Bakr and 'Umar.47 However, the majority of scholars are of the opinion that this version is weak because of the following reasons:

A. It contradicts what came correctly in an exact saying from Anas.

B. It is in opposition to other versions of the same saying, and those other versions are consistent with the two letters of Abu Bakr and 'Umar. Those other versions are sustained by al Baihaqi and others.48

C. This differing version is not consistent with the general rule in zakah collection, that zakah is due in the same kind of the zakatable asset except out of necessity. The case of camels below 25 is an obvious necessity, but it is not necessary to take sheep when the number of zakatable camels is above 120. Another inconsistency in this version is that the increase of five camels from 145 to 150 requires an increase in zakah from a one to two years old female camel to a three to four year old female camel, which makes the rate at this level more than the ratio at other levels.49

Other scholars consider the report of lbn Hazm superseded by those of Abu Bakr and 'Umar. Ibn Taimiyah supports this last view an the basis that Ibn Hazm was given these instructions when he was appointed governor of Najran, some time before the death of the Prophet (p), while the message of Abu Bakr the truthful was written by the Prophet (p), just before he died, and since he did not have a chance to send it to his governors it was sent by Abu Bakr after he succeeded him.50 Thus it seems that Ibn Taimiyah tends to go along with these who consider the instructions of Ibn Hazm cancelled by the later instructions of Abu Bakr and 'Umar, since it is known that the former preceded chronologically the latter.

The view of majority, including; Ahmad, al Shafi'i and al Awza'i, is much stronger and better supported by proofs than that of the Hanafites. Some fair Hanafites even give more weight to the majority view, such as the late 'Abd al 'Alyy al Laknawi, known as the "Ocean of knowledge", from India. In his Rasa'il al Arkan al Arba'ah, pp, 170-171, he says: "What seems to be stronger is the view of al Shafi'i and Ahmad.51

The view of Al Tabari

Abu Ja'far al Tabari expresses a third, reconciling view, stating that both opinions are acceptable, and it is up to the zakah collection agency to select which view to apply.52 In my opinion this is a better approach, since one should not consider the content of a saying superseded and annulled if there is the slightest chance of a reconciliation of all the reports from the Prophet (p). The reconciliation proposed by al Tabari is undoubtedly acceptable if we keep in mind that the determination of ages and quantity of camels due as zakah is meant to facilitate zakah calculation, payment, and collection, and to simplify the procedures so that the zakah collecting agency can exercise some discretion.

The slight differences in the letters of zakah

Looking at the different versions of messages about zakah reported from the Messenger of God (p), and his Wise Successors, one would find some minor differences. An example is whether the difference in value between different age camels is ten dirhams (or two sheep) or twenty dirhams (or two sheep)53. How can the difference between the letter of 'Ali and those of Abu Bakr and 'Umar be explained? It is known that the report of 'Ali is incorrect as linked to the Prophet (p), but it is also known that the version stating that it is a saying of 'Ali himself is correct. How could 'Ali differ with the letter of the Prophet (p)? How could he, who lived the era of Abu Bakr and 'Umar not be aware of their letters and application? Did he believe that he had information which superseded that contained in the other letter?

In my opinion all these questions are answered negatively and it seems to me that another interpretation of those minor differences is due. I believe that some of these equalities, like the value of sheep in silver, are given by the Prophet (p), in his capacity as the head of the state. Their prices at his time were such that a sheep equaled approximately ten dirhams. It is known that prices vary from time to time, and when the Prophet (p), gave the ratio as twenty dirhams for two sheep he was quoting his period's current prices. At the time of 'Ali's caliphate, prices of sheep were different, and his quotation of those prices were ten dirharms for two sheep. This is not a violation of the Prophet's saying, but rather an application of the rule used by the Prophet (p), to what suits the time of 'Ali. This interpretation is, in my opinion, better than any attempt to disregard any of the differing texts, like what Yahya bin Ma'in did in claiming that nothing correct is reported on the determination of rates and quantities of zakah.55 Ibn Hazm came down very hard on such a claim and asked how a person like Ibn Ma'in could state such a thing without even the slightest supporting evidence.56 An Orientalist like Schacht abuses to the utmost that claim in his attempt to reject all the correct sayings on zakah.

SECTION THREE ZAKAH ON COWS

Cows, used by mankind for land cultivation, meat and milk, are another bounty of God on His servants. The usefulness of this species was so great at times that some peoples, such as the ancient Egyptians and contemporary Hindus worshiped this animal.

Buffalo is counted with the cows by all Muslim jurists, as stated by Ibn al Mundhir.

Zakah on cows is obligated by Sunnah and Ijma. Bukhari, in his correct collection, reports from Abu Dharr "I came to the Prophet (p)58 and he said 'I swear by He who holds my soul in His hand,' or 'I swear by the one beside whom there is no God. No man who has camels, cows or sheep and does not pay their right due but on the Day of Judgement will be trampled by them at their largest and heaviest. They will be stepping on him with their hooves and ramming him with their horns, and when the last one is done with him the first is brought back until judgement has been given to all people." Imam al Bukhari said "It is also narrated by Bakir from Abu Saleh from Abu Hurairah from the Prophet (p). The "right due" mentioned in the saying means zakah before any other thing. Zakah is the right due on wealth as defined by Abu Bakr at the time of fighting those who rejected zakah, this definition was approved by 'Umar and all other Companions, (reported by al Bukhari and Muslim). In the version reported by Muslim the word "zakah" is used in place of the word "right due", moreover, Muslims through all generations have unanimously confirmed that zakah is obligated on cows. Not a single scholar disagrees.59 There are however, differences in determining nisab and zakah rates on cows.

Nisab and rates of zakah on cows

There is no correct saying that provides us with the nisab and rates of zakah on cows as we have seen on camels. This may be because cows were rare in the area of Hijaz (around Makkah and Madinah); it may be also because cows are close in size and value to camels, so the Prophet did not determine their rates on the assumption of their obvious similarity. But the fact that there is no correct saying on the issue left the jurists with varying views on the determination of nisab and rates.

The popular opinion: Nisab is 30 cows

The reputed position upheld by the four schools of jurisprudence is that nisab is 30

cows, and there is no obligated zakah on less than 30 cows. For 30 cows, a one-year old cow is due, and for 40 to 59 cows there is one cow, two years old, due. For 60 cows, two one-year-old cows are due; for 70 cows, a one-year-old and a two-year-old; for 80

cows, two two-year olds; for 90 cows, three one- year-olds; for 100 cows, one two-year old and two one-year-olds; for 110, two cows two year olds and one cow one year old, and for 120 cows, three two-year olds or four one-year olds.

This opinion relies on the saying reported by Ahmad and the four books of Sunan al Tirmidhi, al Nasa'i, Abu Daud and Ibn Majah from Masruq from Mu'adh bin Jabal who said "The Messenger of God, (p) sent me to Yemen. He instructed me to collect on each 30 cows, a one year-old cow, and on each 40 cows one two-year-old"60. This saying is graded as good by al Tirmidhi and as correct by Ibn Habban and al Hakim, Ibn 'Abd al Barr comments "Its chain is correct, continuous and authentic" and similar statement is made by Ibn Battal. Ibn Hajar said in al Fath "We need to scrutinise any ruling about the correctness of this saying, because Masruq [The follower] did not meet Mu'adh." al Tirmidhi considers it good because there are other sayings that testify with it, such as the one in al Muwatta, from Taus from Mu'adh, but Taus did not meet Mu'adh either.61

Abu Daud has a similar saying from 'Ali.62 Ibn al Qattan comments on the narration of Masruq from Mu'adh, "It is probable; it should be considered connected in accordance with the majority's view.63 Ibn Hazm first considered this saying weak on the ground that Masruq did not meet Mu'adh, but he later corrected himself and said. "I found that Masruq merely mentioned the practice of Mu'adh in Yemen regarding zakah on cows; there is no doubt that he lived in Mu'adh's era, witnessed his governorship, and recognized his well-known practices. Consequently his quotation of Mu'adh is accepted, because he is quoting many people that witnessed the same practice, a practice that reflected the instructions of the Messenger of God (p), so we must accept that report"64.

Al Hafiz Ibn Hajar in his al Talkhis quotes Ibn 'Abd Al Barr from the latter's al Istidhkar, "There is dispute among scholars that the tradition about zakah on cows is what exists in the saying from Mu'adh. That is the agreed upon nisab"65. The saying of Mu'adh is supported by the letter of the Prophet (p) to 'Amr bin Hazm, which says "and on each 30 cows, one cow one-year-old is due, and on each 40 cows, one cow is due".

Several scholars of hadith consider this last one good.66

It should be noted, however, that both of these sayings do not explicitly set the minimum for zakatability at 30, and that the wording of these two sayings does not prevent the possibility of imposing zakah on less than 30 cows. Thus any claim of Ijma as that of Ibn 'Abd al Barr is rejected, because it is known that Ibn al Musayyeb, al Zuhri, Abu Qulabah, al Tabari and others disagree, as will be shown later. Ibn Hajar quotes al Hafiz 'Abd al Haqq as saying "There is no saying, about nisab of cows on whose correctness there is agreement."67

The saying of Mu'adh also indicates that there is no additional zakah on between 40

and 59 cows, and this is also supported by the report that Mu'adh was brought additional zakah on cows and refused to take it on this number, as mentioned in al Muwatta' and other works. This is the opinion of the three schools of jurisprudence, Abu Yusuf, Mohammad, and the majority of scholars. Abu Hanifah disagrees and expresses the view that what is above 40 cows is zakatable at the rate of two-and-half percent of the price of a cow, two years old, for each additional cow above 40. Al Hasan has another report from Abu Hanifah that additional amounts of zakah are due only when the number reaches 50, whereby one-and- one-quarter cow becomes the due zakah. There is still a third report from Abu Hanifah that goes along with the majority's view.68

The view of al Tabari that nisab is 50

Ibn Jarir al Tabari argues that nisab must be 50 cows, that if is undoubtedly unanimous that for each 50 cows there is an obligatory zakah of one cow. Anything below 50 is controversial and not supported by a clear text.69 Ibn Hazm in al Muhalla supports this opinion on the same grounds as al Tabari. He comments "Anything that is controversial and on which there is no text making it obligatory must not be imposed on people, because it means confiscating a part of a Muslim's wealth without being certain about its requirement by virtue of a correct text from God or His messenger (p).70 He went on to quote, through his own chain, from 'Amr bin Dinar, "The commissioners of Ibn al Zubair as well as Ibn 'Auf used to collect one cow from each 50 cows,71 2 cow from each 100 and for more than that, the rate was one cow out of each 50.72 These commissioners were performing their duties in the presence of many, many Companions in Madinah, and this performance was not objected to.

But one may disprove this opinion on two grounds:

A. From the point of view of the text. The long saying of 'Amr bin Hazm on zakah says "and from each 30 cows, take one cow one-year-old, and from each 40 cows, one cow". This saying is graded good by a handful of leading scholars and it was used by al Tabari against the view of Taqiy al Din bin Daqiq al 'Id in his book Al Imam.73

Additionally, the saying of Mu'adh according to which zakah should be collected on 30

and 40 cows is graded correct by a group of the leading scholars. It is by virtue of this saying that Ibn Hazm corrected himself and reverted to the view of the majority.74

B. From the point of view of the rationale. It is very unlikely that Shari'ah, which is most just and wise, would obligate zakah on only 5 camels or 40 sheep and leave the minimum for zakatability on cows to be 50. Cows may not be as huge as camels, but they certainly are bigger, more useful, and more valuable than sheep.

The opinion of Ibn al Musayyeb and Al Zuhri

Two leading scholars, Said bin al Musayyeb and Muhammad bin Shehab al Zuhri, along with Abu Qulabah and others view nisab on cows to be the same as nisab on camels, and the zakah rate of camels to be the same for cows with only a minor change, that is, disregarding the ages of camels. A similar opinion is reported as a version of the letter of 'Umar bin Al Khattab on zakah, from Jabir bin 'Abd Allah and others who paid zakah at the time of the Prophet (p). Abu 'Ubaid reported from Mohammad bin 'Abd al Rahman that the instructions 'Umar bin al Khattab wrote on zakah included "from cows one should take the same as from camels." Abu 'Ubaid continues "Others were asked about zakah on cows and the answer was it is the same on camels".

Ibn Hazm reports with his own chain from al Zuhri and Qatadah, both from Jabir bin 'Abd Allah his saying that "in each five cows there is one sheep due, in ten two sheep, in 15, three sheep, and in 20, four sheep due." Al Zuhri says "zakah on cows is like zakah on camels except for the ages. That is, if the number of cows were between 25 and 75

the amount of zakah due on it is one cow, between 76 and 120 two cows. Above 120, for an additional 40 cows there is one additional cow. We were told that the statement 'in each 30 cow there is one cow due one year old, and in each 40 cows there is due one cow ' was only a simplification and reduction in the rates for the people of Yemen which was disregarded later."76 It is also reported from 'Ikrimah bin Walid his saying: later I was commissioned on the zakah of 'Ikk and I met some old people who paid zakah at the time of the Messenger of God (p). They disagreed: some of them said make zakah on cows like zakah on camels, and some said from each 30 cows you take one cow, one year old, while yet some others said from each 40 cows you should take one two-year-old cow."76 Ibn Hazm reports through his own chain from Ibn al Musayyib, Abu Qulabah, and another scholar a view similar to that of al Zuhri. He also report from 'Umar bin 'Abd al Rahman bin Khildah al Ansari, "Zakah on cows is the same as zakah on camels except for the ages.77

Evidence supporting this view

A. This opinion is supported by a report of Abu Ubaid with his own chain from Muhammad bin 'Abd al Rahman, "It is in the Prophet's letter on zakah and in the letter of 'Umar bin al Khattab that from cows, one should take the same as from camels."78

Also, this view is supported by what is reported by 'Abd al Razzaq from Ma'mar, who said, " Sammak bin al Fadl gave me a letter from the Prophet, to Malik bin Kuflanis Al Mus'abiyn, in which I read, 'and on cows is due the same as on camels.'"79

B. This is confirmed by what is mentioned by al Zuhri that it was the latest report from the Messenger of God (p), and that taking a one-year-old cow of each 30 cows was, at the beginning, a matter of favor for the peoples of Yemen. This report is mursal, but it is supported by the previous saying and by statements from some Companions.

Ibn Hazm comments "If a mursal saying would be accepted from anyone, it deserves to be accepted from al Zuhri because he was well versed in Suunah and met a number of the Companions".80

C. This view is also supported by the general rule implied in the saying mentioned at the beginning of Section 3 "And for anyone who owns cows and who does not pay their right due, he would be laid down for the cows to trample on the Day of Resurerction" It is argued that this is a general text that includes cows of any number except for restrictions brought in by a text or any Ijma'. It is further argued that the saying stating that there is one cow, one year old, due, on each 30, and a two-year-old due on each 40 also supports this opinion because it does not waive zakah from cows below 30. It is only a statement of the rate of zakah.

D. It is further argued, by analogy, that cows are similar to camels. In 'Id sacrifice, for example, a cow is sufficient for seven individuals, just as a camel. Also in the gifts of thanks to God after pilgrimage , the rate of camels and cows is the same, so zakah on cows should be like that on camels.81

However, Ibn Hazm disproves these arguments on the basis that the sayings attributed to the Prophet (p) are not completely linked to him and one can only give as evidence a saying whose chain is completely linked to the Prophet. He notes that the argument that the saying about zakah on cows is general for any number of cows is binding only an the Hanafites and Malikites who obligate zakah on business assests by generality of texts alone, but not those who require specific text for obligating any ruling in Shari'ah. As for the argument that zakah on cows should be similar to that on camels by analogy, I say that if analogy is accepted as a tool in deducting rulings in Shari'ah, then this application of it is a correct one, since I am aware of no agreed-upon difference between camels and cows. Thus, this conclusion must be binding to those who accept analogy--the Hanafites, Malikites and Shafi'ites, but I do not.82

On the other hand, scholars of the known schools of jurisprudence argue that nisab should not be deducted by analogy; nisab should only come from a text, and it is evident that there is no text on nisab of cows. Ibn Qudamah adds that such an analogy is incorrect, since in sacrifice and pilgrimage, 35 sheep equal five camels, but 35 sheep are not nisab in zakah.83

A fourth opinion

Ibn Rushd gives yet another opinion without providing the name of its author nor its argument: On each ten cows there is one sheep due, until they reach 30 cows, on which there is a one-year-old cow due.84 I find that Ibn Abi Shaibah attributes this view to Shahr bin Haushab in his al Musannaf. The latter says "zakah should be one sheep due on each ten cows, two sheep on each twenty cows, and one cow, one year old, on 30

cows."85 This means that nisab of cows is ten as compared to five in the previously mentioned opinion. No evidence of support is given by Ibn Abi Shaibah. It may come to mind that this argument can be supported by the saying that estimates the compensation for the loss of life at 100 camels or 200 cows. This is reported as said by 'Umar, as well as linked to the Prophet (p).86 This implies that one camel equals two cows. If nisab for camels is five, that of cows must be ten, and if for each five camels the amount of zakah due is one sheep, there should be one sheep due for each ten cows.

Analysis and weighing

After listing all these opinions,87 it seems to ms the view of the majority about the rate on each 30 and 40 cows is the one that carries more weight, on the basis of the saying of Mu'adh and Amr bin Hazm. However, it is notable that these two sayings do not give information about what is below 30 cows, whether negative or positive, but only determine the rate of zakah rather than its nisab, except by contrast. Interestingly enough, the saying of Ibn Hazm goes on to state, "And on each 40 dinars (of gold) there is due one dinar". The majority of jurists agree that nisab on gold is 20 dinar and not 40, which indicates that this saying was given to determine the rate of zakah and not necessarily its nisab, since the rate on gold is two-and-half percent or one-fortieth.

It is possible to combine this opinion with that of Ibn al Musayyib, al Zuhri and their group of followers in putting nisab on cows at five, especially since it is put at five in a version of 'Umar's letter on zakah, as a report from Jabir bin 'Abd Allah, a Companion, and is sometimes attributed to the letter of the Prophet (p). Abu 'Ubaid comments that this opinion was not known by people, but it was shown earlier that it was in fact known to a number of Companions and Followers. Additionally, one can argue that the analogy of cows and camels is a strong one and the objection of Ibn Hazm can be disregarded as based on his personal view that all analogy is invalid. The majority of scholars are in accord on the principle that the correct analogy is a source of deduction in Shari'ah.

God knows best, but it seems to me that the Messenger of God (p), intentionally left certain issues in zakah undefined and undetermined in order to make its application flexible with changing circumstances. It is left to the Islamic state and its zakah institution to draw up those details from time to time. Cows may become more expensive and useful than camels. In this case nisab may be set at five, and the rate of one sheep for each five cows could be applied, and when they number 30's and 40's, the saying from Mu'adh could be applied. This opinion may become more practical and clear when cow raising becomes big and profitable business. In some countries or times, cows may carry lesser value than camels, to the extent that five of them would not be such substantial wealth as to stand as a minimum zakatable, in which case nisab could be put at 30. This flexibility has its root in the comment of al Zuhri that 30 cows as nisab was made only to make things easier for the people of Yemen. Given what al Zuhri said, the sequence in time between letters setting the nisab at 30 and at five does not necessarily imply that the latter annuls the former, but can be interpreted as different applications in two different circumstances by the Prophet (p), in his capacity as head of state and not just as a Messenger. Consequently, for different circumstances he may have even another opinion.89

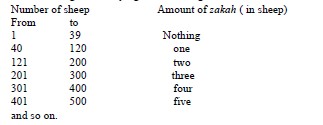

SECTION FOUR ZAKAH ON SHEEP

Zakah on sheep is obligating by virtue of Sunnah and Ijma'. In Sunnah, Anas narrates in the letter of instruction of Abu Bakr mentioned earlier that "As for sadaqah on sheep, naturally cost-free pastured, out of each 40 there is one sheep due, up to 120.

If the number increased, then two sheep are due up to 200, and if the number increases by one up to 300, there are three sheep due. If it is above 300,90 then one sheep is taken for each additional 100. If naturally, cost-free pastured sheep are less than 40, even by only one, there is no obligatory sadaqah on it unless the owner wishes to volunteer, As zakah one should not accept the old, the damaged, or the ram except when volunteered by the owners." Similar statements appear in the saying from Ibn 'Umar and in several others.

Jurists unanimously agree that zakah is obligatory on sheep. There is also unanimous opinion that the word "ghanam" includes both sheep and goats in such a way that they are combined together as one item.91

According to this saying the following table can be drawn:

We will discuss in section 6 the description of what animal should be taken as zakah as for its size, age and sex.

Discussion of the rate on sheep

It is notable that Shari'ah reduced the rate on sheep as their number increases. From the previous schedule it is observed that as the number grows above 120 the rate stabilizes at one percent in contrast with the usual two-and-half percent on business assets, money and other assests. What is the rationale for this reduction? Some contemporary researchers92 attempt to explain this reduction with the argument that Shari'ah intends to encourage animal breeding by this reduction, since the rate on 40

sheep is two-and-half percent and it regresses at 200, going clean to one percent. But one wonders, if this explanation is correct, why the same is not applied on zakah on other kinds of livestock. The rate on both camel and cows stabilizes around two-and half percent on big numbers, which is consistent with the general rate of zakah. If the above-mentioned interpretation is correct, it should apply to other animals as well.

The way I see it --God knows best-- is that once the number of sheep grows, the total assests of sheep shall contain many baby lambs because most sheep give birth more than once a year, These babies are counted in the number of sheep but not accepted as payment of zakah, as shall be shown in the following two sections. It seems to me that the justice requires certain reduction in the rate for this reason. If the rate is kept at one out of each 40 while the herd contains many babies, the actual rate becomes much higher. As for the first 40, the rate is two-and-half percent because it is expected that babies would not be counted in the first 40, as will be explained in Section five.

This shows that the rate of zakah is in fact about constant, not progressive or regressive, which will be discussed at length in the last part of this book. In the commentary on al Risalah, the late Malikkite Sheikh Zarruq writes on the declining rate of zakah on sheep between 40 and 200" once the numbers of sheep grows their cost increases, and the desire for accumulation increases too, therefore, the rate on cash assets is as low as one fourth of ten percent, while it goes up to ten percent on other assets."93 I could not appreciate this argument because when wealth increases its costs decline. This is perhaps why owners of cattle like to pasture together on a large scale, to diffuse the cost of shelter and shepherding. This is known now as the economy of large scale. If the explanation given by Zarruq is correct it should have applied to all cattles but we see the rate not reduced for large quantities of camel and cows.

SECTION FIVE ARE BABY ANIMALS ZAKATABLE ?

Ahmad, Abu Daud, and al Nasa'i report from Suaid Bin Ghaflah that "the zakah commissioner of the Messenger of god (p), came to us. We sat close to him and I heard him saying 'In my instructions it is pleased that I should not take from nursing animals'.94 This indicates that baby livestock are not zakatable, and this is the opinion of a group of leading scholars. But the chain of this saying is contested. On the other hand, Malik in al Muwatta reports that 'Umar told his commissioner, Sufian bin 'Abd Allah al Thaqafi, to "Count the babies in them, even those carried by the shephered in his hands, but do not accept them in payment."95 This is also reported by al Shafi'i and 'Abu Ubaid.96 This report of 'Umar contradicts the previous report and indicates that baby animals are counted in nisab and consequently zakatable. This is what a group of jurists adopt, to the extent that if all the zakatable animals were babies, one of them would be acceptable as payment,"97 though others say the owner should be asked to buy an older animal from outside to fulfil the payment of the zakah.98

Some scholars attempt to reconcile the report of 'Umar with the saying of Suaid by not obligating zakah on baby animals if they comprise the entire zakatable, saying that is where the saying of Suaid applies, while counting baby animals if they are with their mothers. However, some jurists consider that baby animals are counted in the total number of the zakatable herd only if older animals make up the nisab required for zakatability. This is the view of Abu Hanifah, al Shafi'i, Ibn Hazm and others.99 It is, in my opinion, the closest to Islamic justice and it seems to outweigh other views. It violates the principle of justice to exempt from zakah a person who owns, for example, four old camels and collect it from a person who owns five baby camels or four baby lambs, since the latter is less rich than the former. Once nisab is fulfilled by counting adult animals alone, then baby animals can be counted in determining the total number subject to zakah. For larger quantities, the rate structure itself is flexible because it takes stratas of quantities and applies the same rate on the lower and the higher ends of each layer. Thus five camels are zakatable at the rate of one sheep, the same as nine camels.

It seems to me that this was purposefully set up by the Prophet (p) in order to give leeway for the presence of baby animals. It seems that this becomes more apparent in sheep, especially goats, which give birth more than once a year. This is perhaps why the rate of sheep is lower at larger quantities, and becomes one percent after the sheep reach 200 in number.

SECTION SIX CONDITIONS OF ANIMALS GIVEN AS ZAKAH

A few conditions are required of the animals that can be paid as zakah, which include:

1. Free of defects and damage. The animal should be free of illness, bone fracture, old age, or birth and accidental defects or damages. The Qur'an says "and do not aim at getting anything which is bad, in order that out of it ye may spend "100 and the Prophet (p) states "and one should not give an old or defective animal, nor should a collector accept a ram unless the payer wishes to volunteer it". This is part of the saying from Anas. Accepting damaged animals as zakah payment is not fair to the poor and other deserving recipients; it is a bias in favor of the owner, which is improper.

As for the definition of defect or damages, the majority are of the view that it is the same definition used in sales contracts, though some say that anything not accepted for sacrifice is not accepted as zakah.l0l One should mentions unique case where a defected or damaged animal is accepted as zakah, which is if all the animals being zakated have the same defect or damage, such as a common disease. This is because the ordinance of zakah asks payment from what the zakatable person owns without forcing him or her to purchase from outside a good animal only for the payment of zakah.l02

Zakah on Livestock 101

2. Specification of the animal's sex, The animal given as zakah must be a female of the species. This applies only to camels, except in the cases mentioned in the saying from Anas, whereby a male of a higher age group is accepted instead of the due female.

Hanafites accept the payment of male animals on the basis of estimating their value,103

because according to them, the value of the due item can be paid instead of it as shall be discussed, God willing, in Part Five.

As for cows, the text requires male or female, one year old, out of each 30, which is not disputed. However, there is a variation on whether to accept a two-year-old male cow, out of each 40. The majority do not approve of that, while the Hanafites accept it on the grounds that male and female cows are similar in value. Hanafites are also supported by a saying reported by al Tabarani from Ibn 'Abbas "For each 30 cows there is due one cow one year old, and for each 40 one older, male or female".104

With regard to sheep, Hanafites do not distinguish between male and female because of the similarity in price and use and also because the text mentions a sheep due, without distinguishing between male and female.105 Malikites go along with the Hanafites on zakah on sheep, while the Hanbalites do not approve of taking the male sheep as zakah as long as there are females in the herd. This is taken in analogy to camels.107

Furthermore, Malik and al Shafi'i leave it to zakah collectors to select the male or the female animal, depending on which is better for zakah recipients.108 Al Nawawi writes, ''If the male sheep is given as zakah, it is alright, according to the majority of Shafi'ites "It is also Shafi'i's opinion himself. Some Shafi'ites do not approve of this view because of 'Umar's report mentioned earlier, which states "and take the female sheep more than one year old".109 After presenting the different opinion, I select the Hanafite's view with regard to cows and sheep because I think it carries more weight and has more convincing evidence than the others.

3. Age requirement. Sayings give specific ages for zakah on camels and cows which must be complied with, on the ground that taking less or more is unfair with either payers or recipients of zakah. This is agreed upon. As for sheep, there is a variation of opinion. According to Malik, sheep accepted in zakah should be at least one-year-old sheep or goat, in compliance with the saying "our right is at the least one-year-old sheep or goat". Shafi'i and Ahmad believe that what is paid as zakah should be at least one year old for goats and six months old for sheep. This is also reported by Abu Daud and Muhammad, while Abu Hanifah agrees with Malik, although he allows giving of six-month-old sheep on the basis of value.112 I select the view of Ahmad, al Shafi'i, Abu Yousuf and Muhammad, because it has strong proofs.

If the age necessary for payment is not available and other ages are available, how should zakah be paid? Ibn Rushd summarizes the several opinions, "according to Malik the zakah payer is required to buy the necessary animal. Others say the payer should pay a lower-age animal plus compensation at the rate of 20 dirhams or 2 sheep for each one year difference in the age of camels, as mentioned in the letter of Abu Bakr on zakah, and there should be no differences about it. This is also the view of al Shaifi'i and Abu Thawr. Some jurists say that payment must be made of the available age and a compensation for the difference should be paid.113 According to Abu Hanifah, the value of the necessary animal is due. It seems to me, however, that Abu Hanifah's view is also consistent with the saying, because the Prophet (p) estimated the difference in age in his capacity as head of state rather than as religious ordinance, and such estimation varies with time. 'Ali estimated sheep at different prices than the estimation of the Prophet (p).114

4. The average The zakah collector should not take the best or the worst in quality, but the average of the animals owed. Ibn 'Abbas narrates that the Prophet (p) said to Mu'adh, "Avoid the best of people's wealth, and be fearful of the prayer of the oppressed, for there is no curtain between it and God." Ibn Abi Shaibah reports that the Prophet (p) saw among the camels collected as sadaqah, an excellent she-camel. He was furious at the collector and said, "What is this?" The collector answered "I exchanged it for two lesser quality camels". The Prophet said, "Then it is all right."115

This is essentially because zakah is based on fairness to the two parties, payers and recipients, and taking the best or the worst means favoring one of them. However, it is obvious that the worst or the best can be taken on the basis of value at the option of the livestock owner. Abu Daud reports, through his own chain, from the Prophet (p) "There are three things, which whoever fulfills them will taste the sweetness of faith: to worship God alone, realizing that there is no deity but God, to give zakah on your wealth with your soul pleased at paying it year after year... and to give not the old, or the ill or the baby, or the defective animal that give little milk, but to give from the average of your wealth. God does not ask you to give the best of it, nor does He ordain you to give the worst of it."116 As zakah payment, the collector must not take the animal that nurses babies, nor pregnant animals, nor the ram out of sheep, nor the animal that is meant to provide meat for the household of the zakah payer.117 Malik reports in al Muwatta from 'Aishah that 'Umar bin al Khattab passed by the sheep taken as sadaqah, and saw one with big udders and asked, "What is this sheep? "He was answered, "One taken as sadaqah." He replied, "Its owners did not give it pleasantly, so do not force people to turn back, and do not take the best of the wealth of Muslims."118

As an application of this condition, baby animals are not accepted as zakah. When 'Umar bin al Khattab commissioned Sufian bin 'Abd Allah al Thaqafi on zakah, he started counting the baby sheep and was asked "Are you counting these babies while you don't accept them in payment? "When he came back to 'Umar and told him that, 'Umar said, " Yes, count baby sheep, even those which are so young that they must be carried by the shepherd, but do not accept them in payment, nor should you take that which is meant for meat of the household, nursing mother sheep, pregnant sheep, nor the ram. Take only sheep or goat which are one year old." Ahmad, Abu Daud, and al Nasa'i report from a person named Si'r from the two men commissioned by the Messenger of God (p) to collect zakah. They said "The Messenger of God (p) prevented us from taking a pregnant animal". And from Suaid bin Ghafalah "A zakah collector sent by the Messenger of God (p) came to us end I heard him saying 'In the pledged instructions given to me it was written I should not count baby animals'.. and when a man wanted to give him a pregnant she-camel, he refused to accept it".120

SECTION SEVEN THE EFFECT OF MIXING AND PARTNERSHIP ON ZAKAH ON LIVESTOCK

It is common for livestock owners, to put together their cattles in order to save on overhead expenses. Should all gathered livestock be treated as one unit in determining the nisab and rate of zakah? or should they be considered for each owner alone?

To deal with this question one should note that there are two leading forms of collective breeding. One involves keeping the ownership separate and sharing in certain expenses, and the other is when the cattle is owned commonly among the partners. In the latter form, the share of each owner is not determined in number but only as a proportion of the total, whereas in the former each person's own animals are distinguished. These two forms of investing together need not have the same effect on zakatability.

Ibn Rushd in Bidayat al Mujtahid, summarizes the views of jurists according to the following:

Most jurists view mixing animals as affecting the zakatability except for Abu Hanifah and his disciples, who believe that mixing together of animals does not have any effect on nisab or on the applicable rate. Malik, al Shafi'i, and most jurists agree that the group of breeders who mix their cattles together are treated as if they were one owner. Those jurists however differ in two areas: the determination of nisab and the definition of effective mixing together.

It should be noted that the reason for these different opinions is the different interpretation of the saying of the Prophet (p). In the letter on sadaqah the Prophet (p)

said, "What is separate should not be counted together, and what is together may not be counted separately in order to avoid sadaqah, and as far what belongs to two persons, they must settle their account in proportion to their ownership". Those who say that mixing together does not affect the zakah interpret this to mean that the zakah collector should not divide herds owned by one person in such a way that would increase zakah.

For instance, 120 sheep owned by one person should not be divided into three groups of 40 to make zakah three sheep instead of one. They also say that what is owned by one person should not be added to what is owned by another in order to make nisab, such as grouping the herds of two peoples, each with 20 sheep, to make them zakatable as nisab. Al Shafi'i and his disciples interpret this saying to mean that cattle put together are treated as if they were owned by one person, both in the application of nisab and in the determination of the zakah rate. On the other hand, Malik and his students interpret it to mean that if each owner alone has the minimum of nisab then the applicable rate is that of the total and not that which applies on what belongs to each owner alone.122

As for the variation on the definition of mixing together, al Safi'i is of the opinion that mixing animals together means in pasturing, milking, sheltering and watering, to the extent that putting animals together is like partnership. Accordingly, nisab is applied on the total and not on each owner alone. Malik sees effective mix together as where watering, pasturing, sheltering and shepherding are common.123

Ibn Hazm in al Muhalla strongly criticizes the opinion that mixing animal, together affects zakah, on the grounds that this ends up in fact violating the essential texts of zakah. For example, a person who owns less than nisab is exempt from paying zakah, so how could such a person be zakated if he puts his cattle with others? This, according to Ibn Hazm, contradicts the principle of individual responsibility and private ownership, making one person's property affect other persons duties and obligations. This is a violation of the Qur'an and Sunnah.124 It should be noted at last that the view of the Shafites has widest concept of the effect on zakah of mixing the wealth of several owners. They go as far as affecting zakah not only on livestock but also on crops, fruits, silver, and gold money that are mixed.l25 This view may serve as a basis for the treatment of contemporary corporations as the zakah agency may find best, because it provides for simplicity in procedures and thrift in collection expenses.

SECTION EIGHT ZAKAH ON HORSES

Horses used for personal transportation and fighting are exempt from zakah.

It is agreed upon among Muslims that horses owned for the purpose of personal riding, carrying personal loads, and fighting for the sake of God are exempt whether they are naturally pastured or fed in ranches, because they are for personal and household use and are not growing assets in excess of personal needs.126 On the other hand, all Muslims except Zahirites have agreed that horses used as business inventory owned by horses' merchants, are zakatable whether they are naturally pastured or manually fed on the grounds that horses designed for business inventory are commodities, like other business asset.127 It is also agreed upon that horses that are fed by owners most of the year, which are not owned for any of the previously mentioned purposes, are exempt from zakah, because natural free pasturing is a condition for zakatability of animals, according to the majority of scholars.128

Zakatability of naturally pastured horses designated for breeding

There are two opinions on the zakatability of naturally cost-free pastured horses that are designated for breeding and growth. Abu Hanifah believe they are zakatable, provided that not all horses owned are males since in this case they cannot breed.129 The majority of jurists consider these horses exempt from zakah, and this is narrated by Ibn al Mundhir from 'Ali, Ibn 'Amr al Sha'bi, 'Ata, al Husain al Abdi, 'Uamar bin 'Abd al Aziz, al Thawri, Abu Yusuf, Muhammad (the two disciples of Abu Hanifah) Abu Thawr, Abu Khaithamah, and Abu Bakr bin Shaibah. Others attribute this opinion to 'Umar, Malik, al Awza'i, al Laith and Daud.130

Evidence of the majority for the non-zakatability of horses

1. It is reported in the two correct books and in others from Abu Hurairah that the Prophet (p) said " There is no sadaqah obligated on Muslims on their slaves and mares."131 This exemption includes all horses, naturally pastured or not, female or male because it is general.

2. The report of Ahmad, Abu Daud, and al Tirmidhi from Ali from the Prophet (p)

"I waived for you sadaqah on horses and slaves. Pay sadaqah on silver money, one dirham for each 40."132

3. The actions of the Prophet (p) did not include collecting zakah on horses, even though it was collected on camels, cows and sheep. The Messenger is the one who gives the details of the obligation outlined in the Qur'an, and his word and deed indicate that horses are not zakatable.

4. They also argue that livestock that are zakatable are obviously very different from horses and that horses cannot be made zakatable by analogy because of the basic differences in use and in the purpose of owning these different kinds of animals. Horses are obtained for use in fighting, in establishing this religion, and in defense against enemies, so people should be encouraged to obtain them and keep them for such purposes. God says "Against them make ready your strength to the utmost of your power, including seeds of war.133 Horses of war are fighting equipment, like weapons and like other fighting tools are not zakatable as long as they are not used as a commodity for trade.134

Abu Hanifah's opinion and its supporting evidence

Abu Hanifah, who believes that naturally pastured horses are zakatable, provides the following arguments:

Firstly, al Bukhari reports in his correct collection from Abu Hurairah that the Prophet (p) said "Steeds are for a person a source of reward, for another they are a source of sustenance, and for yet another they are a source of sin. He for whom they are a source of reward is the man who owns horses for the purpose of fighting for the sake of God, to ride it in battle or to give it to someone else to ride in battle. That is why they are a source of reward. For one who keeps horses for personal transportation so he does not need others, and does not forget God's right on the horses or the right of people to be given lifts on their backs, they are source of sustenance. And for the person who keeps steeds as a matter of pride and to fight against the people of Islam, they are a source of sin."135 This saying indicates that there is a right of God on horses, zakah and giving lifts on their backs.136 Other jurists argue that what is meant by the right on horses is the use of horses in fighting.137

Secondly, it is reported from Jabir from the Prophet (p), "On each naturally pastured mare there is due one diner or ten dirhams." It is reported by al Daraqutni and al Baihaqi, and they grade it weak. For this reason, the majority of jurists argue that it can not stand against the correct saying of zakah waiving off horses." There is no zakah on the slaves and mares of Muslims." Thirdly, by analogy to camels, both are growing and useful animals, and in both the condition for zakatability, natural cost-free pasturing, is fulfilled. The claimed differences between horses and other livestock are no more than those among the other kinds of livestock, since each animal has its unique characteristics. There are many differences between camels and sheep yet both are zakatable. Abu Hanifah holds to this argument on the basis that the reason for the obligation of zakah is a matter that can be rationalized and not a matter of worship only. This reason is growth or growth potential and once growth exists in another asset zakatability must be extended to it.

Fourthly, al Tahawi and al Daraqutni report, with a correct chain, from al Sa'ib bin Yazid "I witnessed my father evaluating his horses and paying its sadaqah to 'Umar bin al Khattab,138 'Abd al Razzaq and al Bai'aqi report from Ya'la bin Umayah that 'Abd al Rahman, brother of Ya'la, bought a mare from a man in Yemen for the price of 100

camels. The seller felt sorry and went to 'Umar complaining "Ya'la and his brother forced me to sell my mare. 'Umar asked Ya'la to come and meet with him, and he gave 'Umar the true story. 'Umar wondered "Would a steed reach that high a pries in your area? I never realized that a mare would reach that value. Would it be just to take one sheep out of each 40 and not take anything from horses? Collect one dinar per horse".

He then imposed zakah on horses at the rate of one dinar each.139 Ibn Hazm reports, with his own chain, from Ibn Shihab al Zuhri that al Sa'ib bin Yazid told him that he used to bring 'Umar bin al Khattab zakah on horses. Ibn Shiab adds, "'Umar used to collect zakah on horses."140 Anas bin Malik narrates that "'Umar used to collect ten dirhams on each mare and five on each male horse.141 Zaid bin Thibit had similar views to that of 'Umar. During the reign of Marwan bin al Hakam, jurists disputed the zakatability of naturally cost-free pastured horses, and when Marwan consulted the Companion, Abu Hurairah, he narrated the saying "There is no sadaqah on one's slave and one's mare." Marwan turned to Zaid bin Thabit and asked "What do you say, O Abu Said?" Abu Hurairah said, "I wonder at Marwan. I tell him the saying of the Messenger of God (p) and he asks 'What do you say O Abu Sa'id?" Zaid answered "The Messenger of God (p) verily said the truth, but he meant the horse of a fighter for the sake of God.

For a merchant who keeps horses for breeding, they are zakatable." Marwan asked "How much?" He replied "One dinar or ten dirhams on each horse".142 Ibn Zanjawaih in Kitab al Amwal reports with his chain from Taus "I asked Ibn 'Abbas, 'are horses zakatable?' and he answered "There is no sadaqah on the horse of the fighter for the sake of God,"143 which implies that other horses are zakatable. Ibrahim al Nakha'i, a Follower, had the same view as 'Umar and Zaid. He said "Naturally pastured horses raised for breeding are zakatable at one dinar or ten dirhams on each horse, or else evaluate them and pay ten dirhams for each 200 dirhams of their value." Mentioned by Muhammad in al 'Athar, Abu Yusuf reports a similar statement,l44 also from Hamad bin Abu Sulaiman that he said and horses are zakatable."145

Nisab and rates of zakah on horses

Abu Hanifah does not determine a nisab for horses. The author of al Durr al Mukhtar writes "It is best known that Abu Hanifah does not estimate nisab for horses; we have no report from him about that."146 Ibn 'Abidin in his commentary quotes al Qahastani as saying "Some indicate nisab at three and others indicate it at five."147 It seems that the estimation of five is mare correct because of its similarity to that of camels. The number five is often used in nisab . nisab is five camels, five 'uqiyyah of silver [equals 200 dirhams] and 5 wasq of grain.

The rate is explained by Ibn Abidin from Abu Hanifah: Owners of Arabian horses are given the choice of paying one dinar on each or evaluating their horses and paying 5

dirhams for each 200 dirhams of value - the rate is just two-and-half. For non-arabian horses, only the value is considered.148

Analysis