QuranCourse.com

Muslim governments have betrayed our brothers and sisters in G4ZA, standing by as the merciless slaughter unfolds before their eyes. No current nation-state will defend G4ZA—only a true Khilafah, like that of the Khulafah Rashideen, can bring justice. Spread this message to every Muslim It is time to unite the Ummah, establish Allah's swth's deen through Khilafah and revive the Ummah!

On Being Human by Osman Latiff

3. Who And What Do We See?

The Power Of An Image

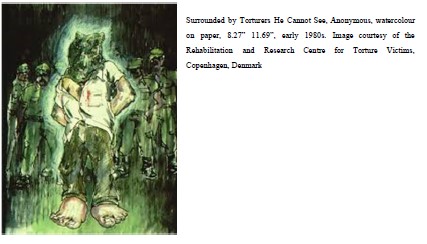

How we see ourselves and how we imagine ourselves being seen has a bearing on our self-identity and on the relationship between ‘self’ and ‘other’. This is reflected visually here in an evocative image entitled ‘The Fear Is Still Me’ (see below). The image suggests a bestial persona of a tortured prisoner donning a hood that conceals his bear-like identity.18

Though “he cannot see” he is very much to be seen as a centre-piece as if heralded by the prison guards. In the image, there appears a halo. We wonder whether the halo etched around him is the beam of a torch from behind him, a floodlight shining onto him or whether the artist challenges us to consider binary oppositions wherein symbols of humanised and dehumanised life become juxtaposed. The togetherness of the guards behind him is set against the isolation of the prisoner though the pack-like formation of the guards and the lone bear-like prisoner is strikingly ironic. It is the wounded bear-like prisoner who has been hunted and the prison guards herald him.

There is much to be seen. The cartoon suggests a larger-than-life individual though his protruding feet perhaps reflect limbs swollen by beating, and in this the prisoner appears imbalanced. Since however his feet bear no injuries might they instead or simultaneously suggest his stamped presence? We cannot see his hands however and imagine what injuries they might bear.

The scruffy clothes of the prisoner with shirt buttons and trouser zip undone are a further contrast to the ‘civilised’ and neat attire of the prison guards. The fact that the prisoner is hooded reveals a lack of self-identity. Though, in place of his assumed fear, worry and pain, the bear-like hood projects defiance and strength.

Undoubtedly, Muslims face a constant barrage of press reports that vilify their faith or other Muslims. This constant othering heightens anxieties and comes to shape the way we see ourselves as a people largely defined through violence. Motifs of barbarity, backwardness, images of women in hijab or burqa framed around narratives of fear and the unknown are commonplace. Butler notes that ‘the frames through which we apprehend or, indeed, fail to apprehend the lives of others as lost or injured (lose-able or injurable) are politically saturated. They are themselves operations of power. They do not unilaterally decide the conditions of appearance, but their aim is nevertheless to delimit the sphere of appearance itself.’19

Tudor (2011) strikes the following example to reflect how attitudes and perceptions of others have a strong bearing on sympathetic or empathic outlooks. Though cautioning against generalisations, he writes:

“When a torturer looks upon his victim he can certainly directly see agony in his face and humiliation in his posture. The problem, though, is the light in which he sees it. It is not a matter of the torturer needing to infer a little further to another, ‘more inner’ realm in which the ‘moral properties’ of the Other’s situation will be revealed. It is a matter of how he sees the Other’s condition. The torturer has the reality of the Other’s suffering squarely in front of him, under a clear light – but that light is somehow wrong. It is a peculiarly cold and harsh light, one that flattens and exposes the Other, cuts and holds him open, all the better to probe and toy with him. What is needed is a different light.”20

Tudor points out that the different ‘light’ will not reveal any new information about the Other, it is about how we perceive that Other. We are required, he reminds us, to “come to the place or attitude from which that direct perception can be had.” Srikanth writes of a ‘post-concentration-camp world’ and questions the extent to which we had learned about the fuller implications of dehumanised life and whether we can conceive of any correlation between the space of Holocaust concentration camps and the space of Guantanamo Bay.

Since there is, she surmises, a hypervisibiity and immediate availability of Holocaust representations through visual representations, films, testimony of Holocaust survivors and written accounts, as well as a preserving of a rescuing role of Western liberators, “We cannot engage in the type of introspection that might lead us to acknowledge the eerie similarity between the national sentiment that led to the establishment of Guantanamo Bay and that which resulted in the concentration camps. The externalization of the Holocaust and the abundance of materials that are at hand to evoke analysis and discussion about it allow us to feel complacent that we will not cross that boundary into antipathy and inhumanity.”21

Former Army Reserve Spc. Kayla Williams describes her experience whilst stationed at Tal-Afar air base in 2003 wherein she was exposed to interrogation methods used on Iraqi prisoners in a unit named ‘The Cage’. Williams stated how the experience had an emotionally debilitating effect on her, forcing her to question what it means of our own humanness if we strip others of their humanity. Though at parts in her memoir she struggles with the pressures of understanding native attitudes, suggesting a larger disconnect between American aspirations and Iraqi attitudes of culture, self-determination and occupation, her thoughts are often juxtaposed by an empathic imagined storying, “It also made me think,” Williams says, “what are we as humans, that we do this to each other? It made me question my humanity and the humanity of all Americans.” Williams attempts to place someone else, someone familiar to her to pursue a mode of human recognisability with someone else, lost in the frame of a collectivised (in)humanity. The prisoner in his isolated appearance does much to allow Williams’ empathic outlook. Un-stereotyped – through association, the Iraqi prisoner can exist in a human-ised frame. She imagines: “While I am watching them do these things to the prisoner, I think a lot about Rick. I imagine what it would be like for him in a situation like this. Especially with a woman here to watch. How much it would distress him. The face is not the same, but the prisoner’s eyes look a lot like Rick’s. The same shape of eyes, the same eye colour. The same lashes…What would it be like for him? As I watch, I imagine Rick. I imagine Rick in this room.”22 Williams has the ability of constructing Self/Other identities through place-making. She imagines Rick in the same room. One’s perceiving of another’s joy or sorrow lies at the root of empathy. Herbert Kelman reminds us that to humanise someone is to “perceive him as an individual, independent and distinguishable from others, capable of making choices…”23 This focus on individualising is a crucial component of empathy. Away from reliance on a stereotype about a group, empathy mandates a seeing in another the individual components that make up one’s self. The same way one’s predispositions to err or one’s likes and dislikes are a necessary part of one’s self then so too must they exist in the Other. This would mean an acceptance of being disagreed with or even in being disliked. The idea is to see the Other as a complex human being. To be genuinely curious about another person and to realise that experiences affect different people in different ways. It is to not to be presumptuous about one person’s attitude and viewpoints due to an attitude formed about the group to which the Other belongs, or because of views his ‘in-group’ has formed about one’s self that is a requirement of empathy.24 This latter consideration is the third component of empathy which Halpern describes: ‘cognitive openness, and tolerating the ambivalence this might arouse.’ Since dehumanising others can be caused by one stereotyping of an entire group, the process of rehumanising others by individualising them through empathy requires far more effort.25

Reel Bad Arabs

Lendenman’s (1983) research has revealed successive negative portrayals of Arabs in political cartoons in American newspapers such as The Washington Post, The Washington Star, The Miami News, The Baltimore Sun and others. Palmer’s (1995) analysis of political cartoons in The Washington Post following Israel’s wars of 1956, 1957 and 1973, the Palestinian Intifida. Even prior to the first Gulf War, there was reflected the same tendency of negative and dehumanising portrayals of Arabs, and oftentimes specifically Palestinian Arabs. Such negative images are often used to promote American wars, or in the case of Palmer’s (1995) analysis, to promote Israel’s campaigns against Palestinians.26 Nasir’s (1979) study of the portrayal of Arabs in American movies between 1894 and 1960

revealed a predominant image of Arabs as backwards, evil and inhumane.27 In Shaheen’s comprehensive study of over 900 Hollywood movies released between 1896 and 2001, a dominant trend of media presentations of Arabs as the dehumanised villain is evident.28

Similarly, Kamalipour (2000) assessed the negative portrayal of Arabs in radio, television, and movies, revealing how Arabs are prone to committing acts of terrorism against Americans.29 Further works by Ayish (1994) and Qazzaz (1975) showed how such mythical images of Arabs as inherently evil, violent, uncultured and threatening are prominent in social science textbooks in elementary school, junior high and high school, which perpetuated negative stereotypes about Arabs.30

There needs to be an unmasking, a successive peeling away of an imagination disfigured by hostility. Edward Said has written:

“The Arab appears as an oversexed degenerate, capable, it is true, of cleverly devious intrigues, but essentially sadistic, treacherous, low…In news reels and or newspapers, the Arab is always shown in large numbers. No individuality, no personal characteristics or experiences. Most of the pictures represent mass rage and misery, or irrational (hence hopelessly eccentric) gestures.”31

Said states that “these contemporary Orientalist attitudes flood the press and the popular mind. Arabs, for example, are thought of as camel riding, terroristic, hook-nosed, venal lechers whose undeserved wealth is an affront to real civilization”.32 What is suggested is a metaphysical distinction between ‘good’ and ‘evil’ as Butler has outlined in relation to the Iraq War and the 2004 Abu Ghraib prison abuse photos. This “demonizes non-western Others and justifies the imperialist logic of ‘new humanitarian wars’ against those ‘Others’ (2006).

The very conception of the human is brought into question; it is not simply “that some humans are treated as humans, and others are dehumanized; it is rather that dehumanization becomes the condition for the production of the human to the extent that a “western” civilization defines itself over and against a population understood as definitionally illegitimate, if not dubiously human.”33

Edward Said makes reference to Lebanese writer Sania Hamady’s work Temperament and Character, in which she homogenises Arab peoples and their societies and thus eradicates their plurality and differences. The only difference he notes about Arab people is that they are set apart from everyone else in their negative characterisation.

“The Arabs so far have demonstrated an incapacity for disciplined and abiding unity. They experience collective outbursts of enthusiasm but do not pursue patiently collective endeavours, which are usually embraced half-heartedly. They show lack of coordination and harmony in organization and function, nor have they revealed an ability for cooperation. Any collective action for common benefit or mutual profit is alien to them.”34

Such simplistic broad brushing of an entire race is not only puerile, it also puts into play an Othering of Arabs akin to that of Jews in Nazi Germany. There is no mention of what the “enthusiasm” might be or the “collective endeavours”, or the “coordination”, or the “cooperation”, or the type of “collective action”, or the type of “common benefit”. In its vagueness, Arabs too appear vague and without purpose. Said comments on the Othering the above excerpt posits of the Arab peoples:

“The style of this prose tells more perhaps than Hamady intends. Verbs like “demonstrate,” “reveal,” “show,” are used without an indirect object: to whom are the Arabs revealing, demonstrating, showing? To no one in particular, obviously, but to everyone in general. This is another way of saying that these truths are self-evident only to a privileged or initiated observer. since nowhere does Hamady cite generally available evidence for her observations.

Besides, given the inanity of the observations, what sort of evidence could there be? As her prose moves along, her tone increases in confidence-: “Any collective action ... is alien to them.” The categories harden, the assertions are more unyielding, and the Arabs have been totally transformed from people into no more than the putative subject of Hamady’s style.”35

Humans seek dignity in being respected and this is something Allāh affords man in his core, human state. This is crucial in our own understanding of ourselves and of others. The way we seek to protect our own dignity gives us an insight into the way others too value themselves and the mode of respect that needs to exist between people. This attitude of living with the bearing of dignity is even more essential in times of conflict and when people are at their most vulnerable. This sense of promoting and respecting a person’s dignity is pivotal in calling others to Allah since it challenges any attitudes of superiority that can easily act as a barrier to the Muslim’s sincerity. This approach from the Muslim prevents his interactions with others disintegrating into a battle of egos. Any attempt at informing them of Islam at that point is simply lost in translation. Sometimes even ‘retreating’, or holding back can be so much more worthwhile than feeling a need to say something at every junction. For this end, it is said that knowledge is knowing what to say, wisdom is knowing when to say it, and that good character is knowing how to say it.

18 Kahleen McCullough-Zander and Sharyn Larson, ‘The Fear Is Still Me’ - http://www.nursingcenter.com/upload/static/230543/fear.pdf.

19 Judith Butler (2010) ‘Performative Agency’ in Journal of Cultural Economy, 3:2, p. 1.

20 K. Tudor (2011). Understanding Empathy. Transactional Analysis Journal, 41(1), 39–57. Garber: 2004, p. 83.

21 R. Srikanth, Constructing the Enemy: Empathy/Antipathy in U.S. Literature and Law (Philadelphia, Temple University Press: 2012), p. 158.

22 Kayla Williams, Love My Rifle More Than You (W.W. Norton, 2006), p. 249.

23 Herbert Kelman, “Violence Without Moral Restraint: Reflections on the Dehumanization of Victims and Victimizers”, Journal of Social Issues, Vol. 29, No.4, (1973), p. 48.

24 Jodi Halpern and Harvey M. Weinstein, Rehumanizing the Other: Empathy and Reconciliation, Human Rights Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 3 (Aug., 2004), pp. 568-9.

25 Jodi Halpern, From Detached Concern to Empathy: Humanizing Medical Practice 1 7-18 (2001 ), pp. 130-133;143.

26 A. Palmer, (1995). The Arab image in newspaper cartoon. In Y. R. Kamalipour (Ed.), The U.S. media and the Middle East: Image and perception (pp. 139-150). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. 27 S. Nasir, (1979). The Arabs and the English. New York: Longman.

28 J. Shaheen (2001). Reel bad Arabs: How Hollywood vilifies a people. New York: Olive Branch Press.

29 Y. R. Kamalipour (2000). Media images of the Middle East in the U.S. In L. A. Gher & H. Y. Amin (Eds.), Civic discourse and digital age communication in the Middle East (pp. 55-70). Stamford, CT: Ablex.

30 M. Ayish (1994). Arab image in American mass media. (In Arabic). Research Series, no 2. United Arab Emirates: United Arab Emirates University; A. Al-Qazzaz (1975). Images of the Arab in American social science textbooks. In B. Abu-Laban & F. Zeadey (Eds.), Arabs in America myths and realities (pp. 113-132). Wilmette, IL: The Medina University Press.

31 Edward W. Said, Orientalism (Vintage,1979): 278-279.

32 Ibid, p. 108.

33 J. Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London, 2006), p. 278.

34 Sania Hamady, Temperament and Character of the Arabs (New York: Twayne Publishers, 1960), p. 100.

35 Edward Said, Orientalism (Vintage,1979), p. 310.

Reference: On Being Human - Osman Latiff

Build with love by StudioToronto.ca