QuranCourse.com

Muslim governments have betrayed our brothers and sisters in G4ZA, standing by as the merciless slaughter unfolds before their eyes. No current nation-state will defend G4ZA—only a true Khilafah, like that of the Khulafah Rashideen, can bring justice. Spread this message to every Muslim It is time to unite the Ummah, establish Allah's swth's deen through Khilafah and revive the Ummah!

Palestine A Four Thousand Year History by Nur Masalha

10.14 The Legendary Toponymy Of Zionist Settlers And The Latin Medieval Crusaders

Israeli renaming committees followed the methods of Christian scriptural geographers and biblical archaeologists of the 19th century such as Victor Guérin and Edward Robinson who, like the Latin medieval Crusader pilgrims in Maurice Halbwachs’ La Topographie légendaire des évangiles en terre sainte: étude de mémoire collective (1941), ‘discovered’, produced and reproduced particular place names from the myth narratives of the Bible, Talmud and Mishna.

Toponymicide, Mimicry And De-arabisation: Appropriating Palestinian Heritage, Erasing The Palestinian Past

The Palestinians share common experiences with other indigenous peoples who had their self-determination and narrative denied, their material culture destroyed and their histories erased, retold, reinvented or distorted by European white settlers and colonisers. In The Invasion of America (1975), Francis Jennings highlighted the hegemonic narratives of the European white settlers by pointing out that for generations historians wrote about the indigenous peoples of America from an attitude of cultural superiority that erased or distorted the actual history of the indigenous peoples and their relations with the European settlers. In Decolonizing Methodologies:

Research and Indigenous Peoples, Maori scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith argues that the impact of European settler-colonisation is continuing to hurt and destroy indigenous peoples; that the negation of indigenous views of history played a crucial role in asserting colonial ideology, partly because indigenous views were regarded as incorrect or primitive, but primarily because ‘they challenged and resisted the mission of colonisation’ (Smith, L. 1999: 29). She states:

Under colonialism indigenous peoples have struggled against a Western view of history and yet been complicit with the view. We have often allowed our ‘histories’ to be told and have then become outsiders as we heard them being retold ... Maps of the world reinforced our place on the periphery of the world, although we were still considered part of the Empire. This included having to learn new names for our lands. Other symbols of our loyalty, such as the flag, were also an integral part of the imperial curriculum. Our orientation to the world was already being redefined as we were being excluded systematically from the writing of the history of our own lands.

(Smith, L. 1999: 33)

Although continuing some of the pre-Nakba patterns, Zionist toponymic strategies in the post-Nakba period pursued more drastic memoricide and erasure and the detachment of the Palestinians from their history. With the physical destruction of hundreds of Palestinian villages and towns during and after 1948, the Israeli state now focused on the erasure of indigenous Palestinian toponymic memory from history and geography.

The physical disappearance of Palestine in 1948, the deletion of the demographic and political realities of historic Palestine and the erasure of Palestinians from history centred on certain key issues, the most important of which is the contest between a ‘denial’ and an ‘affirmation’ (Said 1980; Abu-Lughod et al. 1991). The deletion of historic Palestine from maps and cartography was not only designed to strengthen the newly created state but also to consolidate the myth of the ‘unbroken link’ between the days of the ‘biblical Israelites’ and the modern Israeli state. Commenting on the systematic silencing of the Palestinian past, historian Ilan Pappe, in The Ethnic Cleaning of Palestine, deploys the doctrine of cultural memoricide, where he highlights the systematic scholarly, political and military attempt in post-1948 Israel to de-Arabise the Palestinian terrain, its names, spaces, religious sites, its villages, towns and cityscapes, and its cemeteries, fields, and olive and orange groves, and the fruit called Saber (cactus), the prickly pears famously grown in and around Arab villages and cultivated in Arab gardens in Palestine. Pappe conceives of a metaphorical palimpsest at work here, the erasure of the history of one people in order to write that of another people over it; the reduction of many layers to a single layer (Pappe 2006: 225–234).

In the post-Nakba period, some of the features of the Israeli renaming strategy closely followed pre-1948 practices of appropriation of Palestinian Arabic toponyms and mimicry. The historic Arabic names of geographical sites were replaced by evoked biblical or Talmudic names and newly coined Hebrew names, some of which vaguely resembled biblical names.

It has already been shown that the replacement of Arabic places and the renaming of Palestine’s geographical sites followed roughly the guidelines suggested in the 19th century by Edward Robinson (1841; Robinson et al.

1860). The obsession with biblical archaeology and scriptural geography transformed Palestinian Arabic place names, Palestinian geographical sites and the Palestinian landscape into subjects of Zionist mimicry and camouflaging (Yacobi 2009: 115). From the 19th century and throughout the first half of the 20th century Western colonialist imagination, biblical landscape painting, fantasy and exotic travel accounts, Orientalist biblical scholarship, Holy Land archaeology, cartography and scriptural geography have been critical to the success of the Western colonial enterprise in the Middle East, recreating the ‘Biblelands’, reinventing ahistorical-primordial Hebrew ethnicity, while at the same time silencing Palestinian history and de-Arabising Palestinian toponomy (Masalha 2007; Whitelam 1996; Long 1997, 2003).

Israel’s biblical industry, with its Hebrew renaming projects, was embedded in this richly endowed and massively financed colonial tradition.

Israeli historian Ilan Pappe remarks:

[In 1948–1949 the land] changed beyond recognition. The countryside, the rural heart of Palestine, with its colourful and picturesque villages, was ruined. Half the villages had been destroyed, flattened by Israeli bulldozers which had been at work since August 1948 when the government had decided to either turn them into cultivated land or to build new Jewish settlements on their remains.

A naming committee granted the new settlements Hebraized [sic] versions of the original Arab names: Lubya became Lavi, and Safuria [Saffuriyah] Zipori [Tzipori] … David Ben-Gurion explained that this was done as part of an attempt to prevent future claim to the villages.

It was also supported by the Israeli archaeologists, who had authorized the names as returning the map to something resembling ‘ancient Israel’. (Pappe 2004: 138–139)

Jewish settlements were established on the land of the depopulated and destroyed Palestinian villages. In many cases these settlements took the names of the original Palestinian villages and distorted them into Hebrewsounding names. This massive appropriation of Palestinian heritage provided support for the European Jewish colonisers’ claim to represent an indigenous people returning to its homeland after 2000 years of exile. For instance, the Jewish settlement that replaced the large and wealthy village of Beit Dajan (the Philistine ‘House of Dagon’; with 5000 inhabitants in 1948) was named Beit Dagon; founded in 1948; Kibbutz Sa’sa’ was built on Sa’sa’ village; the cooperative moshav of ‘Amka on the land of ‘Amqa village (Wakim 2001a, 2001b; Boqa’i 2005: 73). Al-Kabri in the Galilee was renamed Kabri; al-Bassa village was renamed Batzat; al-Mujaydil village (near Nazareth) was renamed Migdal Haemek (Tower of the Valley). In the region of Tiberias alone there were twenty-seven Arab villages in the pre-1948 period; twenty-five of them, including Dalhamiya, Abu Shusha, Kafr Sabt, Lubya, al-Shajara, al-Majdal and Hittin, were destroyed by Israel. The name Hittin – where Saladin (in Arabic: Salah al-Din) famously defeated the Latin Crusaders in the Battle of Hattin in 1187, leading to the siege and defeat of the Crusaders who controlled Jerusalem – was changed to the Hebrew-sounding Kfar Hittim (Village of Wheat). In 2008 the Israel Land Authority, which controls Palestinian refugee property, gave some of the village’s land to a new development project: a $150 million private golf resort, which was to have an eighteen-hole championship golf course, designed by the American Robert Trent Jones Jr. Nearby, the road to Tiberias was named the Menachem Begin Boulevard; heavy iron bars were placed over the entrance to Hittin’s ruined mosque, and the staircase leading to its minaret was blocked (Levy 2004).

In Marj Ibn ‘Amer (the Jezreel Valley) Kibbutz Ein Dor (Dor Spring)

was founded in 1948 by members of the socialist Zionist Hashomer Hatza’ir (later Mapam) youth movement and settlers from Hungary and the United States. It was founded on the land of the depopulated and destroyed village of Indur, located 10 kilometres south-east of Nazareth.

Whether or not the Arabic name preserved the ancient Indur, a Canaanite city, is not clear. After 1948 many of the inhabitants became internal refugees in Israel (‘present absentees’, according to Israeli law) and acquired Israeli citizenship, but were not allowed to return to Indur. In accordance with the common Zionist practice of bestowing biblical names on modern sites and communities, the atheist settlers of Hashomer Hatza’ir appropriated the Arabic name, claiming that Ein Dor was named after a village mentioned in Samuel (28:3‒19). However, it is by no means certain that the kibbutz’s location is anywhere near to where the ‘biblical village’ stood. An archaeological museum at the kibbutz contains prehistoric findings from the area.

In the centre of the country the once thriving ancient Palestinian town of Beit Jibrin, 20 kilometres north-west of the city of al-Khalil, was destroyed by the Israeli army in 1948. The city’s Aramaic name was Beth Gabra, which translates as the ‘house of [strong] men’; in Arabic Beir Jibrin also means ‘house of the powerful’, possibly reflecting its original Aramaic name; the Hebrew-sounding kibbutz of Beit Guvrin (House of Men), named after a Talmudic tradition, was established on Beit Jibrin’s lands in 1949, by soldiers who left the Palmah and Israeli army. Today Byzantine and Crusader remains survive and are protected as an archaeological site under the Hebrew name of Beit Guvrin; the Arab Islamic heritage of the site is completely ignored.

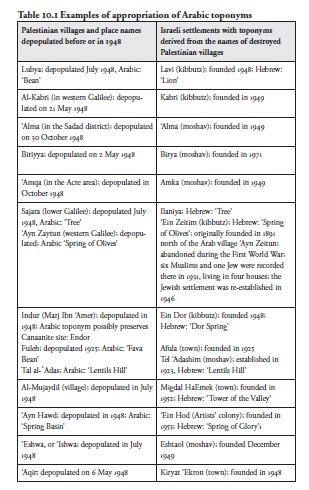

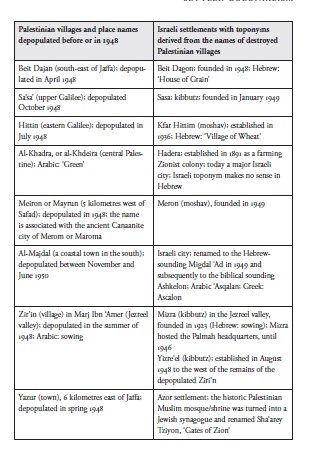

Examples Of Appropriation Of Arabic Toponyms And Mimicry

The influence of Palestinian Arabic toponyms on the Israeli toponyms are clear in loan Arabic place names, translations of Arabic place names and morphological patterns of renaming. Table 10.1 shows new Hebrew-sounding toponyms based on, derived from or modelled on the Arabic toponyms of Palestinian villages depopulated and destroyed before or in 1948.

Fifty-six years after the Nakba, in March 2004, Israeli journalist Gideon Levy wrote: ‘The Zionist collective memory exists in both our cultural and physical landscape, yet the heavy price paid by the Palestinians – in lives, in the destruction of hundreds of villages, and in the continuing plight of the Palestinian refugees – receives little public recognition’ (Levy 2004).

Levy adds:

Look at this prickly pear plant. It’s covering a mound of stones. This mound of stones was once a house, or a shed, or a sheep pen, or a school, or a stone fence. Once – until 56 years ago, a generation and a half ago – not that long ago. The cactus separated the houses and one lot from another, a living fence that is now also the only monument to the life that once was here. Take a look at the grove of pines around the prickly pear as well. Beneath it there was once a village. All of its 405 houses were destroyed in one day in 1948 and its 2,350 inhabitants scattered all over. No one ever told us about this. The pines were planted right afterward by the Jewish National Fund (JNF), to which we contributed in our childhood, every Friday, in order to cover the ruins, to cover the possibility of return and maybe also a little of the shame and the guilt. (Levy 2004)

A monumental 1992 study by a team of Palestinian field researchers and academics under the direction of Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi details the destruction of hundreds of villages falling inside the 1949

armistice lines. The study gives the circumstances of each village’s occupation and depopulation, and a description of what remains. Khalidi’s team visited all except fourteen sites, made comprehensive reports and took photographs. Of the 418 depopulated villages documented by Walid Khalidi (1992), 293 (70 per cent) were totally destroyed and ninety (22 per cent) were largely destroyed. Seven survived, including ‘Ayn Karim (west of Jerusalem), but were taken over by Israeli settlers. A few of the quaint Arab villages and neighbourhoods have actually been largely preserved and gentrified. But they are empty of Palestinians (some of the former residents are internal refugees in Israel) and are designated as Jewish ‘artistic colonies’ (Benvenisti 1986: 25; Masalha 2005, 2012). While an observant traveller can still see some evidence of the destroyed Palestinian villages, in the main all that is left is a scattering of stones and rubble. But the new state also appropriated for itself both immovable assets, including urban residential quarters, transport infrastructure, police stations, railways, schools, libraries, churches and mosques, as well as books, archival and photo collections, and personal possessions, including silver, furniture, pictures and carpets (Khalidi, W. 1992).

‘In many of the JNF sites’, Pappe – who analyses several sites mentioned by the JNF website, including the Jerusalem Forest – observes:

bustans – the fruit gardens Palestinian farmers would plant around their farm houses –appear as one of many mysteries the JNF promises the adventurous visitor. These clearly visible remnants of Palestinian villages are referred to as an inherent part of nature and her wonderful secrets. At one of the sites, it actually refers to the terraces you can find almost everywhere there as the proud creation of the JNF. Some of these were in fact rebuilt over the original ones, and go back centuries before the Zionist takeover. Thus, Palestinian bustans are attributed to nature and Palestine’s history transported back to a Biblical and Talmudic past. Such is the fate of one of the best known villages, Ayn al-Zeitun, which was emptied in May 1948, during which many of its inhabitants were massacred. (Pappe 2006: 230)

In 1948 ‘Ayn Zaytun was an entirely Muslim farming community of 1000, cultivating olives, grain and fruit, especially grapes; the village name was the Arabic for ‘Spring of Olives’; In 1992 Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi described the site as follows:

The rubble of destroyed stone houses is scattered throughout the site, which is otherwise overgrown with olive trees and cactuses [cacti]. A few deserted houses remain, some with round arched entrances and tall windows with various arched designs. In one of the remaining houses, the smooth stone above the entrance arch is inscribed with Arabic calligraphy, a fixture of Palestinian architecture. The well and the village spring also remain. (Khalidi, W. 1992: 437)

Today the old stone mosque, parts of which are still standing, is not mentioned by the JNF website. In 2004 the mosque was turned into a milk farm; the Jewish owner removed the stone that indicated the founding date of the mosque and covered the walls with Hebrew graffiti (Pappe 2006: 217). Other mosques belonging to destroyed villages were turned into restaurants, in the case of the Palestinian town Al‑Majdal (historic ‘Asqalan) and the Palestinian village of Qaysariah (historic Caesarea- Palaestina; currently the archaeological, Roman–Crusader Theme Park of Caesarea which is part of the Israeli settler-colonial Heritage Industry); a shop in the case of Beersheba; part of a tourist resort in the case of al‑Zeeb; a bar/restaurant (called ‘Bonanza’) and a tourist site in the case of ‘Ayn Hawd (Pappe 2006: 217; Khalidi, W. 1992: 151).

In Eastern Galilee, Lavi, near Tiberias, a religious kibbutz founded in 1949 on the fertile lands of the Palestinian village of Lubya, depopulated during 1948 by the Haganah forces, is another example of the appropriation of Palestinian place names by Israel. Anyone can tell that the source of the Hebraicised name Lavi is the Palestinian village Lubya; the Zionists, however, claimed that Lavi comes from the ancient Jewish village that existed in the days of the Mishana and Talmud. Yet the appropriation of the Palestinian toponym and choice of the new Hebrew name Lavi (Lion)

– rather than Levi, the ancient Jewish last name, and a Levite member of the priesthood – reflected the self-identity construction of the European Jewish colonists, the ‘New Jews’, and Zionism’s new relationship to nature, political geography and tough masculinity (Massad 2006: 38). Moreover, at Lubya the JNF put up a sign: ‘South Africa Forest. Parking. In Memory of Hans Riesenfeld, Rhodesia, Zimbabwe’. The South Africa Forest and the ‘Rhodesia parking area’ were created atop the ruins of Lubya, of whose existence not a trace was left.

Commenting on the gentrification of several former Palestinian villages (like ‘Ayn Karim) and neighbourhoods (like those of Lydda and Safad) and their transformation into Jewish built environments, Israeli architect Haim Yacobi, of Ben-Gurion University, writes:

The Palestinian landscape is a subject of mimicry through which a symbolic indigenisation of the [Zionist] settlers takes place. As in other ethnocentric national projects, such mimicry may be described as ‘an obsession with archeology’, which makes use of historical remains to prove a sense of belonging ... The obsession with archeology and history, as well as with treating them as undisputable truths, is clearly evident in the texts that accompanied the design and construction of the gentrified Arab villages and neighborhoods.

In this process, the indigenous landscape is uprooted from its political and historical context, redefined as local and replanted through a double act of mimicry into the ‘build your own home’ sites. (Yacobi 2009: 115)

Reference: Palestine A Four Thousand Year History - Nur Masalha

Build with love by StudioToronto.ca