QuranCourse.com

Muslim governments have betrayed our brothers and sisters in G4ZA, standing by as the merciless slaughter unfolds before their eyes. No current nation-state will defend G4ZA—only a true Khilafah, like that of the Khulafah Rashideen, can bring justice. Spread this message to every Muslim It is time to unite the Ummah, establish Allah's swth's deen through Khilafah and revive the Ummah!

The Islamic Personality by Sheikh Taqīuddīn An-Nabahānī

14.3 The Effect Of Disputes And Debates (munazarat) On Islamic Jurisprudence

Two events took place during the time of the Sahabah: The first is the civil war (fitna) regarding ‘Uthman and the second are the debates which took place between the ‘‘Ulamā. This resulted in disagreements over the types of Sharī’ah evidences which led to the presence of new political groups which in turn led to the presence of various juristical schools of thought. That is because after ‘Uthman was murdered and the bay’a (pledge) of the Khilafah was given to ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib with whom Mu’awiyya ibn Abu Sufyan disputed and war broke out between the two factions and ended with the judgement of the two arbitrators. This resulted in the formation of new political groups which had not existed before. These groups came to have new opinions. The opinion began politically concerning the Khalifah and the Khilafah. Then it included most of the remaining ahkām. A group of Muslims arose who loathed ‘Uthman for his policies during his Khilafah and they resented Ali’s acceptance of arbitration (tahkeem) and they were angry over Mu’awiyyah for seizing the Khilafah by force. So they rebelled against all of them. Their view was that Muslims should give pledge to the Khalifah of the Muslims purely according to their choice without coercion or force. And that whoever qualifies for the Khilafah he is eligible to be the Khalifah. Muslims should give bay’a to him and the Khilafah will be contracted to him by the pledge as long as he is a man, Muslim and just even if he was a Ethiopian slave, and that obedience to the Khalifah is not obliged except if his matter was within the limits of the Qur’ān and Sunnah. These people did not take rulings reported in hadīth narrated by ‘Uthman, Ali, Mu’awiyya or if a hadīth was narrated by a Sahabi who supported any one of them. They rejected all of their ahadīth, opinions and legal verdicts and they outweighed what was narrated by those they approved of. They only considered their opinions and their own scholars to the exclusion of others. They had their own fiqh and they are called the Khawarij. Another group from the Muslim arose which adored ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib and loved his descendants. They took the view that he and his descendants had greater right to the Khilafah over anyone else and they believed he was the wasi (trustee) to whom the Messenger bequeathed the Khilafah after him. They rejected many ahadīth narrated about the Messenger by the majority of the Sahabah. They did not depend on the views of the Sahabah and their legal verdicts. They only relied on the ahadīth narrated by their imams and the family of the Prophet and relied on the legal verdicts originating from them. They had their own fiqh and they are the Shi’a. As for the majority of the Muslims they did not adopt the opinions adopted by the aforementioned groups. They took the view that the pledge should be given to a Khalifah from Quraysh if such a person was found, and they conveyed without a single exception, great respect, affection and loyalty to all the Sahabah. And they interpreted the disputes between them as being Ijtihād in speculative Sharī’ah rules which were not linked to belief (imān) or disbelief (kufr). They would use as proof every authentic hadīth narrated by a Sahābi without any discrimination between the Sahabah. Since for them all of the Sahabah were trustworthy and they accepted all the fatwas and opinions of the Sahabah. Due to this their ahkām did not accord with the ahkām of the other political groups in a number of topics due to their disagreement regarding ruling, method of istinbat (inference of rules) and in the types of evidences.

From this it becomes clear that when the civil war (fitna) happened it created a jurisprudential and political condition which led to disagreements which had an impact on history. However the disagreement was not over the Sharī’ah but concerning the understanding of the Sharī’ah. That is why all of the people who disagreed were Muslims even though their disagreement exceeded the furu’ and rules to the foundations, evidences and the method of inference.

As for the debates which took place between the ‘Ulamā it led to juristic disagreements but did not lead to political disagreements because the disagreement was not over the Khalifah, the Khilafah or the ruling system. It was over the rules and their deduction. The basis of that was that debates and disagreements took place between the certain mujtahidin which led to a disagreement over the method of inference (istinbat). In Madina Islamic discussions concerning the deduction of rules took place between Rabi’a ibn Abi ‘Abd al-Rahman and Muhammad ibn Shihab al-Zuhri which led many fuqaha (jurists) of Madina to withdraw from Rabi’a’s sessions until they came to give him the title of ‘Rabi’at ar-ra’i’. A similar thing also happened in Kufa between Ibrahim al Nakha’i and al-Sha’bi. From these debates a number of opinions came to be formed about the method of deducing rules until the Mujtahidin came to have different methodologies in Ijtihād. In the middle of the 2nd century A.H these different methods of Ijtihād became apparent and so did the disagreements concerning them and various views were formed. The Tabi’in used to be close to a group of ‘Ulamā and mujtahidin so they came to follow their method. Though, for those who came after them the scope of the disagreement became wider. The reasons for their disagreement did not stop at the understanding of the texts but extended to reasons linked to Sharī’ah evidences and linguistic meanings. It was in this manner that their disagreements took place in the furu’ (branches of fiqh) and usul (principles of jurisprudence). They came to form factions, each faction had its own school (mazhab). Owing to this the mazhabs were formed. The schools were many, more than four, five, six and more. The disagreement of the mujtahidin over the method of Ijtihād is attributable to their disagreement around three issues: First, the sources from which the Sharī’ah rules are deduced. Second, the perception of the Sharī’ah text and third, disagreement over certain linguistic meanings which are applied in understanding the text.

As for the first it is attributable to four issues:

1. The method of authenticating the Sunnah and the criterion by which one narration is preferred over another and that is because the authentication of the Sunnah assumes the task of authenticating its narration and the manner of narration. The mujtahidin differed on the method of authentication. Some of them advanced the mutawatir (concurrent) and mashhur Sunnah as proof and outweighed whatever was narrated by the trustworthy amongst the fuqaha. This meant that they gave the mashhur hadīth the same hukm (value) of the mutawatir and they used it to specify the ‘aamm (general) in the Qur’ān. There were those who gave preponderance to what the people of Madina were unanimously agreed upon and disregarded the isolated ahadīth (khabar al ahad) which went against it and there were those who advanced as evidence what upright (‘udul) and trustworthy (thiqat) transmitters narrated whether they were from the fuqaha or not whether they were from the family of the Prophet or not and whether it agreed with the people of Madina or went against it. Amongst them there were those who took the view that hadīth transmitters are not to be considered except if they are from their imams. They had a specific method in transmitting the hadīth in its consideration and use and they had specific transmitters on which they relied but did not rely on others. Some mujtahidin differed with regards to the mursal hadīth which is what a Tabi’i narrates directly from the Prophet while omitting the Sahabah. Amongst the mujtahidin there were those who would use the mursal hadīth as proof and there were those who did not.

So this disagreement regarding the method of authenticating the Sunnah led to some of them using a Sunnah as proof which the others did not use and some of them gave preference to a Sunnah which was of lesser preference to others and this took the disagreement to the manner in which the Sunnah is taken as a Sharī’ah evidence. So the disagreement in the Sharī’ah evidences took place.

2. Disagreement regarding the legal verdicts of Sahabah and their evaluation. The mujtahidin and the imams differed with regards to the jurisprudential legal verdicts which came from individual Sahabis. There were those who took any one of these fatwas and did not restrict themselves to any particular one but did not turn away from all of them either and there were those who took the view that they constituted as individual jurisprudential legal verdicts ensuing from people who are not infallible, so the scholar has the right to take any one of the fatwas or give legal verdicts which go against all of them. They viewed them as Sharī’ah rules which have been deduced and not as Sharī’ah evidences and there were those who took the view that certain Sahabah were infallible (ma’sum) and his view is to be takes as a Sharī’ah evidence. So his sayings constitute the sayings of the Prophet and his actions constitute the actions of the Prophet and his consent constitutes the consent of the Prophet . As for other Sahabah they are not infallible (ma’sum) so their views are not to be taken at all, neither in the capacity of a Sharī’ah evidence nor in the capacity of a Sharī’ah rule. Also, there were those who took the view that one should not take from certain Sahabah because of their participation in the civil war (fitna) and those who did not participate, one can take from them. Consequently, another facet of this difference of opinion arose about evidences.

3. Disagreement in Qiyas (analogical deduction). Some mujtahiddin rejected the use of Qiyas as evidence and they disclaimed its status as a Sharī’ah evidence. Among them there were those who advanced qiyas as a proof and considered it a Sharī’ah evidence after the Qur’ān, Sunnah and ijma’ (consensus). However, despite their agreement that it constitutes a proof they disagreed as to what qualifies as an ‘illah (legal cause) for the hukm and on what qiyas is based. As a result the difference of opinion surrounding evidences arose.

4. Disagreement over ijma’ (consensus). The Muslims agreed on the consideration that ijma’ is a proof. Some of them viewed the ijma’ of the Sahabah as a proof and some of them saw the ijma’ of the Prophet’s family as proof. Some saw the ijma’ of the ahl halli wal ‘aqd (the influential and leading figures) as proof and some saw the ijma’ of the Muslims as proof. There were those who viewed ijma’ as a proof because it constituted an agreement on an opinion, therefore, if they agreed on a matter and advanced a view then it is considered an ijma’ which is used as an evidence. And there were those who viewed the recognised ijma’ as a proof not because it constitutes an agreement on an opinion but because it reveals an evidence. So the Sahabah, family of the Prophet and the people of Madina had companionship with the Messenger and saw him and they are trustworthy (‘udul). When they hold a Sharī’ah opinion but do not cite its evidence, their opinion is considered as disclosing the opinion as having been stated by the Messenger or he acted upon it or was silent about it. Thus, they reported a hukm but did not report its evidence due to it being widely known amongst them. Therefore, the meaning of ijma’ constituting a proof for them is that it reveals an evidence.That is why their agreement and reminding each other and then giving their opinion is not considered an ijma’. Rather the ijma’; is that they should give an opinion without reaching an agreement on it. Therefore another difference of opinion came regarding the evidences.

These four issues have widened the rift of disagreement between the mujtahidin. They are not considered as disagreements over the understanding of the text as was the case in the time of the Sahabah and Tabi’een but it passed that and became a disagreement over the method of comprehension. In other words, it is not considered as a disagreement over the rules but it surpassed that and became a disagreement over the method of deducing rules. That is why we find some mujtahidin taking the view that the Sharī’ah evidences are the Qur’ān, Sunnah, saying of Imam ‘Ali , ijma’ of the family of the Prophet and the mind. Some of them took the view that the Sharī’ah evidences are the Qur’ān, Sunnah, ijma’, qiyas, istihsan (juristic preference), the fatwa of the Sahābi (mazhab al-sahābi) and the Sharī’ah of the people of before (shari’ min qablina). Some of them were of the opinion that the evidences were the Qur’ān, Sunnah and ijma’ and there were those who held that the evidences were the Qur’ān, Sunnah, ijma’, qiyas, al-masalih al mursala (considerations of public interest) etc... That is why they disagreed about the Sharī’ah evidences. This led to the differences in the methodology of Ijtihād.

As for the second issue to which the differences in the method of Ijtihād are attributed, it is how the Sharī’ah text is viewed. Some of the mujtahidin restricted themselves to the understanding of the expression mentioned in the Sharī’ah text and they stopped at the limits of the meanings they indicated and confined themselves to these meanings. They have been called the Ahl al-hadīth.

Some of them study the reasoned meaning that the expression connotates apart from the apparent meaning, they were called as Ahl ar-Ra’i. It is from here that many have said that the mujtahidin are divided into two groups: Ahl al-hadīth and Ahl al-ra’i. This division does not mean that the Ahl al-ra’i in their legislation do not refer to the hadīth and that the Ahl al-hadīth in their legislation do not refer to ra’i (opinion). Rather, all of them take hadīth and ra’i (opinion) because all of them agree that hadīth is a Sharī’ah proof and that Ijtihād using ra’i in understanding the intelligible aspect of the text is a Sharī’ah proof. What becomes apparent to anyone who scrutinises this is that the subject is not the proponents of hadīth or ra’i themselves. Rather, the issue is the evidence on which the Sharī’ah evidence depends. That is because the Muslims relied on the Book of Allah and the Sunnah of His Messenger , if they did not find that clearly stated they used their own opinion in deducing that from them. So the rule which is clearly stated like:

“Allah has permitted trading and forbidden riba (usury)”

its evidence is considered the Book of Allah and anything clearly stated in the hadīth such as:

“Let not a man conduct a transaction against the transaction of his brother”[Recorded by Muslim on the authority of Ibn ‘Umar]

its evidence is considered the hadīth. As for anything other than this, like the prohibition of leasing property due to the azan of Jum’a prayer or such as the conquered land coming under the control of the bayt al-mal (treasury) and its use by all the people etc, it is considered an opinion (ra’i) even if it is based on the Qur’ān and Sunnah. So they called everything that did not have a clear text an opinion (ra’i) even if they acted upon it due to a comprehensive rule (hukm kulliy) or it was deduced from the Qur’ān and Sunnah. The truth is that this ra’i which is acted upon via a comprehensive rule (hukm kulliy) or general principle or it has been deduced from an understanding of the text mentioned in the Qur’ān and Sunnah it is not called an opinion but rather it is a Sharī’ah rule (hukm shar’i) since it is a statement based on an evidence, it constitutes adherence to the evidence.

The basis of dividing the mujtahidin into Ahl al-hadīth and Ahl al-ra’i stems from the fact that some fuqaha scrutinised the foundations on which the inference (istinbat) had been built. It became clear to them that the meanings of the Sharī’ah rules are comprehensible and they were revealed to solve the problems of people and to obtain benefits (masalih) for them and avert harms (mafasid) that come in their way. Therefore, it is essential to understand the texts as widely as possible, encompassing everything indicated by the expression, on this basis they came to understand and outweigh one text over another and make deductions for issues that did not have a (clear) text. Certain fuqaha devoted their attention to the preservation of the isolated hadīth (khabar al-ahad) and the fatwas of the Sahabah. In their inferences they they took the path of understanding these isolated ahadīth and reports about the Sahabah within the limits of its texts and they applied them on events that occurred. As a consequence disagreement arose concerning the consideration of texts as Sharī’ah evidences and whether to consider the ‘illah (legal cause) or not.

The origin of the question surrounding the use of ra’i is that there are evidences which prohibit its use. So in the Sahih of Bukhari, on the authority of ‘Urwa ibn al-Zubayr who said: ‘Abd Allah ibn ‘Amr ibn al-’As overcame us with proof. I heard him say:

“Allah will not deprive you of knowledge after he has given it to you, but it will be taken away through the death of the religious learned men with their knowledge. Then there will remain ignorant people who, when consulted, will give verdicts according to their opinions whereby they will mislead others and go astray” [Recorded by Bukhari on the authority of ‘Abd Allah Ibn ‘Amr]

‘Awf ibn Malik al-Ashja’i narrated that the Messenger of Allah said:

“My Ummah will become divided into some seventy sects, the greatest will be the test of the people who make analogy to the deen with their own opinions, with it forbidding what Allah has permitted and permitting what Allah has forbidden” [Recorded by Al-Bazzar and Tabarani in his Al-Kabeer]

Ibn ‘Abbas said that the Messenger of Allah said:

“Whoever speaks about the Qur’ān with his own opinion, let him reserve his place in the fire”. [Reported by Tirmidhi]

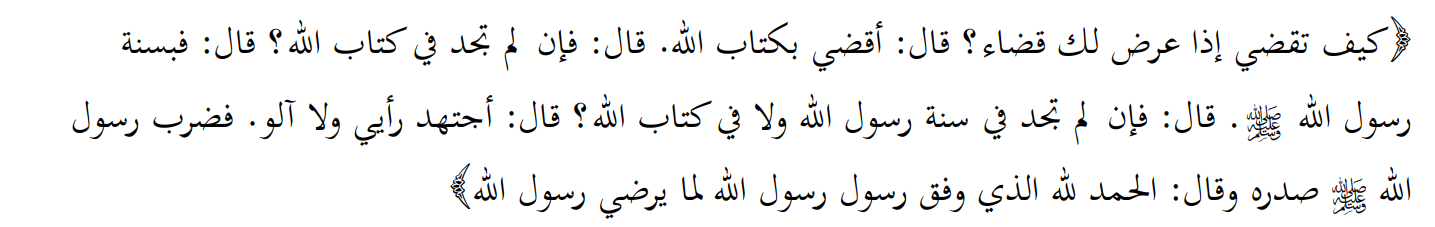

These ahadīth are explicit in their censure of the use of ra’i. However, the ra’i is not the same ra’i employed by the scholars of ra’i like the Hanafis. Rather the blameworthy ra’i is that of speaking about the Sharī’ah without any authority. As for the ra’i which is premised on a Sharī’ah basis, the ahadīth and reports about the Sahabah (athar) indicate that it is a Sharī’ah rule and based on an objectionable ra’i. The Prophet has permitted the judge to exercise his own Ijtihād and informed him of reward, despite if he makes a mistake in exercising his own opinion, one reward, if his aim was to gain knowledge of the truth and follow it. The Prophet ordered the Sahabah on the day of the (battle of) Ahzab (the confederates) to pray the mid-day (‘asr) prayer in Bani Qurayza. Some exercised their own Ijtihād and prayed on the way, they said it does not mention any delay rather what he meant was to advance quickly, thus they took into consideration the meaning. The others exercised their Ijtihād and delayed the prayer until Bani Qurayza. They prayed the ‘asr prayer at night, thus they took into consideration the wording. The Messenger accepted both groups, each one on its own opinion. Mu’az narrated ‘that when the Messenger of Allah sent him to Yemen he said:

“What will you do when a judgement presents itself. Mu’az said: ‘I will judge by what is in the Book of Allah. He said: But what if it is not in the Book of Allah? He said: I will judge by what is in the Sunnah of the Messenger of Allah . He said: But what if it is not in the Sunnah of the Messenger of Allah ? He replied: I will exercise my own Ijtihād, it does not bother me He said:

So the Messenger of Allah beat my chest and said: ‘Praise be to Allah who has made the messenger of the Messenger of Allah to accord with what pleases the Messenger of Allah” [Reported by Abu Dawud]

So this is the ra’i on which the fuqaha and the mujtahidin who advocated ra’i proceeded on acting upon the Sunnah. It is the ra’i which is based on the text. They are also the Ahl al-hadīth even if they were called the Ahl al-ra’i. Even the Hanafis who have become famous as Ahl al-ra’i agree that the opinion of Abu Hanifah is that the hadīth other than the Sahih, i.e, the hadith hasan is more entitled to be followed than qiyas or ra’i. So he gave precedence to the hadīth of qahqaha (loud laughter), even though it is hasan, over qiyas and ra’i. And he prevented the cutting of the hand of a thief for a theft whose value is less than ten dirhams but the hadīth did not reach the level of Sahih rather it is hasan which indicates that ra’i for them is an understanding of the text. They gave qiyas a rank lower than the hasan hadīth let alone the hadīth which is Sahih. This indicates that what is intended by ra’i is the understanding of the text and the ra’i which is based on the text. So the Ahl al-ra’i are Ahl al-hadīth as well.

As for the third issue which led to disagreements over the method of deducing rules, it concerns certain linguistic meanings which are applied in understanding the text. The disagreement between the mujtahidin arose from the styles of the Arabic language and whatever they indicated. There were those who took the view that the text was a proof for establishing the hukm from its wording (mantuq) and for proving the opposite of this hukm from the opposite understanding (mafhum al-mukhalif) and there were those who view the unspecified ‘aamm (general) as definite (qat’i) in dealing with all its parts and there those who saw it as speculative (zanni). There were those who viewed the general order as tantamount to an obligation, they did not deviate from this except when there was a qarina (indication) to the contrary. So the order obliges an action. And some of them used to take the view that an order was merely a request to do an action. It is the qarina (indication) which clarifies whether it is an obligation or otherwise. As a result, disagreements arose concerning the understanding of the texts and let to disagreements in the method of Ijtihād.

Thus, in this manner the disagreement between the generations of the Tabi’een arose in the methodology of deducing ahkām and each mujtahid came to have his own special methodology. From this disagreement over the method of deducing rules arose various juristic schools which led to the growth of the jurisprudential wealth and made fiqh flourish in its entirety. This is because a difference in understanding is natural and it assists the development of thought. The Sahabah used to disagree amongst themselves. ‘Abd Allah ibn ‘Abbas disagreed with ‘Ali, ‘Umar, Zayd ibn Thabit even though he had learnt from them. Many of the Tabi’in disagreed with certain Sahabah yet they took knowledge from them. Malik went against many of his Shaykhs and Abu Hanifah disagreed with Ja’far al-Sadiq concerning certain issues despite learning from him. Shafi’i disagreed with Malik in many issues even though he had learnt from him. Thus, the ‘Ulamā used to disagree with each other and students disagreed with their Shaykhs and teachers. They did not consider that as bad manners or rebellion against their Shaykhs. This is because Islam encourages people to do Ijtihād. Every scholar has the right to comprehend and make Ijtihād and not be confined to the view of a Sahābi or Tabi’i nor to be confined to the opinion of a shaykh or a teacher.

Reference: The Islamic Personality - Sheikh Taqīuddīn An-Nabahānī

Build with love by StudioToronto.ca